Web scraping and web crawling get thrown around like they mean the same thing. They don't.

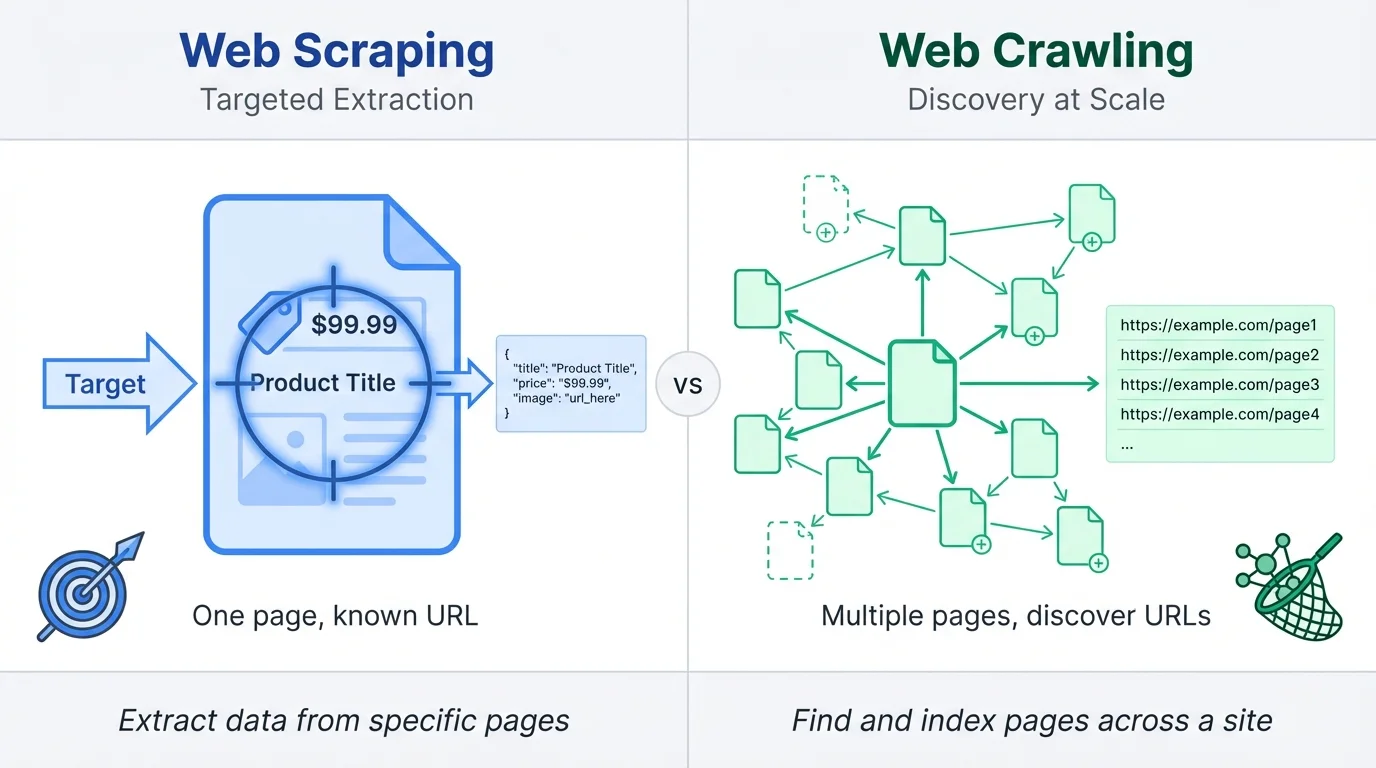

A scraper extracts data from a specific page. A crawler navigates across multiple pages or entire websites. One targets a single URL, the other maps out a whole site. Knowing when to use which saves you from building the wrong solution.

This guide breaks down the difference between scrapers and crawlers, explains how each works under the hood, and walks you through two practical projects: a job listing extractor (scraping) and a blog content collector (crawling). Both projects use Firecrawl, so you can run the code yourself.

By the end, you'll know exactly which approach fits your use case.

Web scraper vs web crawler: the core difference

Here's how they compare at a glance:

| Web Scraping | Web Crawling | |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | Single page or specific URLs | Entire website or multiple sites |

| Primary goal | Extract specific data | Discover and index pages |

| Output | Structured data (JSON, CSV, database) | List of URLs or page content |

| Speed | Fast (targets known pages) | Slower (must traverse links) |

| Use case example | Pull product prices from one page | Index all products across a site |

| Analogy | Fishing with a spear | Fishing with a net |

A simple way to remember it: scraping is about what's on a page, while crawling is about finding pages.

A web scraper targets pages you already know about. You give it a URL, tell it what data you want (prices, titles, descriptions), and it extracts that information into a structured format. The scraper doesn't care what other pages exist on the site.

A web crawler, on the other hand, starts with one or more seed URLs and follows links to discover new pages. Search engines like Google use crawlers to find and index the web. The crawler's job is navigation and discovery first, with data collection as a secondary step.

The confusion between these terms exists because many tools do both, and in practice, the two techniques often work together. When someone says "I scraped that website," they might mean they crawled it first to discover all the product URLs, then scraped each page for specific details.

Think of crawling as the reconnaissance phase and scraping as the extraction phase.

What is web scraping

A scraper grabs data from pages you already know about. You point it at a URL, tell it what to extract, and it hands you structured data:

- Send a request to the target URL

- Get back HTML (or wait for JavaScript to render)

- Parse the page and locate the elements you care about

- Pull the data into a usable format

- Store it somewhere (JSON, CSV, database, whatever)

Simple enough until you hit a modern, dynamic website.

Most sites today load content through JavaScript, so the HTML you get from a basic request is a skeleton with empty divs. You need a headless browser (Puppeteer, Playwright) to let the page fully render before you can see what's actually there.

Parsing is where you spend most of your time. CSS selectors work for straightforward layouts. XPath handles messier DOM structures. Some newer tools, like Firecrawl, use AI to identify fields without manual selectors (you can use natural language), which saves you from rewriting everything when a site tweaks its layout.

For a deeper dive into scraping fundamentals, check out this web scraping intro for beginners.

What is web crawling

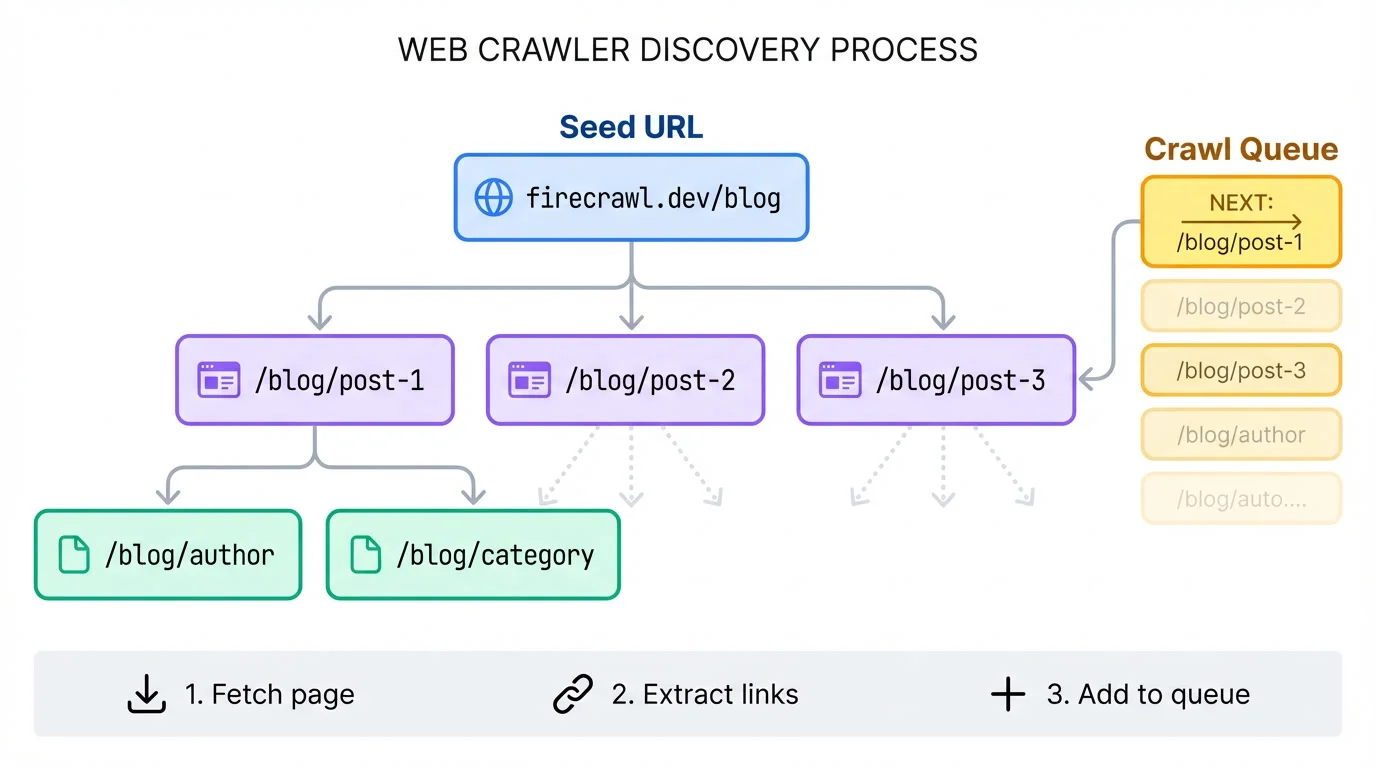

Think of a crawler as a scraper that doesn't know where to go yet.

You give it a starting URL, and it figures out the rest by fetching a page, pulling out every link, adding new ones to a queue, and repeating.

A crawler pointed at a blog's homepage will find links to posts, then links within those posts, then maybe links to author pages or categories. It keeps going until you tell it to stop.

That stopping condition matters. Set a limit of 50 pages, a max depth of 3 links from the start, or a URL pattern like "only follow /blog/* paths." Without boundaries, you'll crawl forever or accidentally wander off to external sites.

The order of crawling changes what you get. Breadth-first stays shallow and wide, visiting everything on the homepage before going deeper. Depth-first picks one path and follows it all the way down. Most site-mapping jobs want breadth-first. Most "find that one buried page" jobs want depth-first.

Deduplication saves you from yourself. Sites love having five URLs that point to the same page (query strings, trailing slashes, tracking parameters). Your crawler needs to recognize these or it'll waste half its time revisiting content.

One more thing: be polite. Check robots.txt, throttle your requests, use a real user agent. Hammering a site with rapid-fire requests gets you blocked and annoys the people running it.

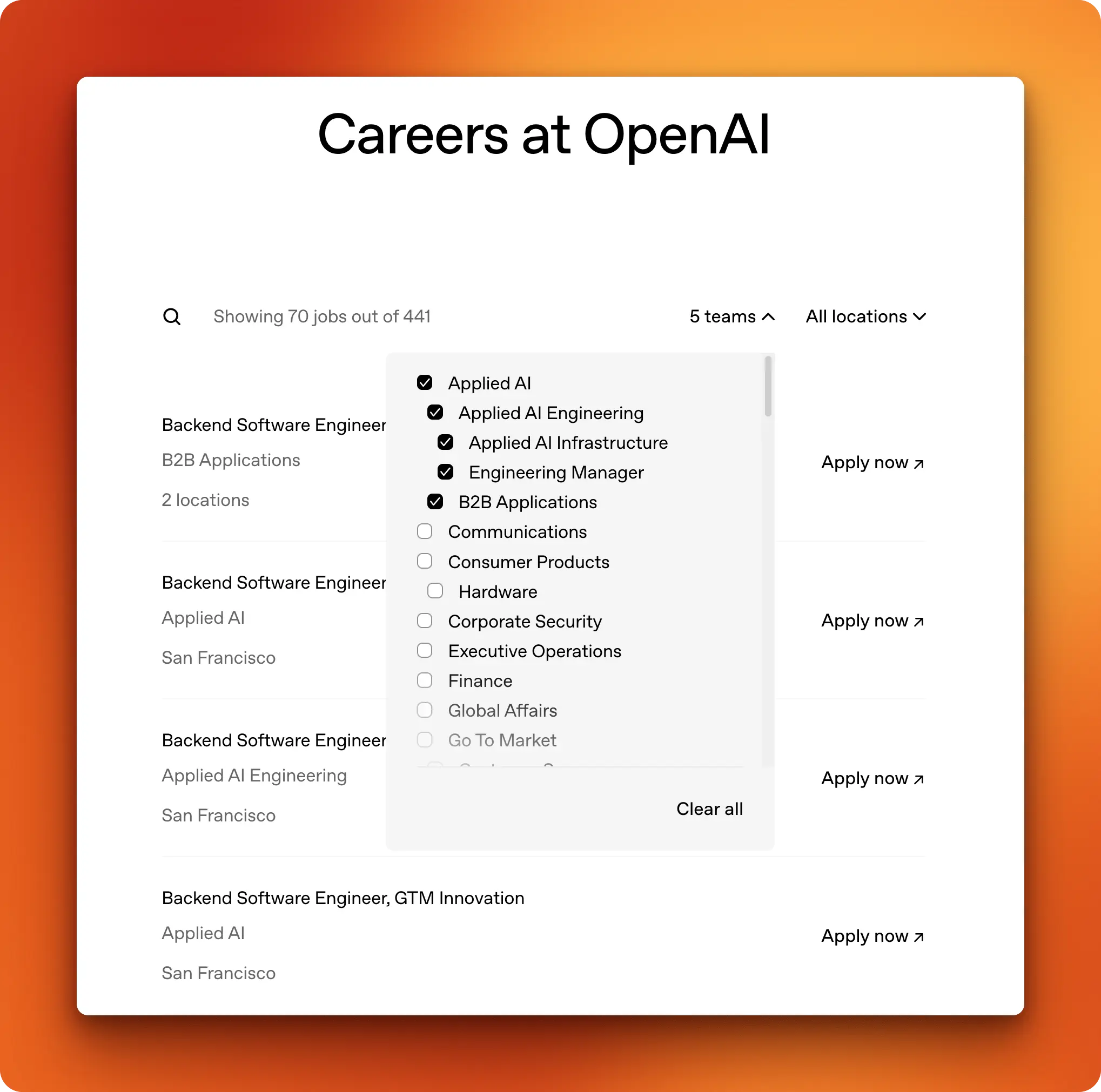

Web scraping in action: Job listing extractor

Time to put scraping into practice. We'll build a job listing extractor that pulls openings from OpenAI's careers page and saves them to a CSV file.

At the time of writing this article, OpenAI has over 400 open positions, so we'll apply the "Applied AI" filter on their careers page to narrow it down. The filtered URL looks messy (filter tokens get encoded), and these tokens can rotate.

If you're following along, visit openai.com/careers/search, apply your own filters, and copy the URL from your browser.

The traditional approach and its problems

A standard scraping workflow would look like this: send a request, get the HTML, find the right CSS selectors for job titles, teams, and locations, then parse everything into a list.

But OpenAI's careers page is JavaScript-heavy.

A basic HTTP request returns an empty shell because the job listings load dynamically. You'd need a headless browser like Playwright to render the page first.

Even with rendering solved, you're stuck with brittle selectors. The job title might be in a div.job-title today and a span.position-name next month. Every site redesign breaks your scraper.

We'll use Firecrawl to solve both problems.

Firecrawl renders JavaScript automatically and uses LLM-based extraction instead of CSS selectors. The scrape endpoint handles single-page extraction with built-in JS rendering. You describe what data you want in a schema, and the LLM figures out where to find it on the page. If the site layout changes, the extraction still works because the LLM adapts to new structures.

Firecrawl offers a free tier with 500 credits to start. If you prefer self-hosting, it's also open source.

Setup

Install the dependencies:

pip install firecrawl python-dotenv pandas pydanticGet your API key from firecrawl.dev and add it to a .env file:

FIRECRAWL_API_KEY=fc-your-api-key-hereDefining the extraction schema

Define your target structure with Pydantic:

from firecrawl import FirecrawlApp

from pydantic import BaseModel

from dotenv import load_dotenv

import pandas as pd

import os

load_dotenv()

app = FirecrawlApp(api_key=os.getenv("FIRECRAWL_API_KEY"))

url = "https://openai.com/careers/search/?c=e1e973fe-6f0a-475f-9362..."

class JobListing(BaseModel):

title: str

team: str

location: str

url: str

class JobListings(BaseModel):

jobs: list[JobListing]The JobListing class defines the four fields we want for each job. JobListings wraps them in a list since we're extracting multiple items from one page.

Scraping with structured extraction

One API call handles both the scraping and the extraction:

result = app.v1.scrape_url(

url,

formats=["extract"],

extract={

"prompt": "Extract all job listings with title, team, location, and URL.",

"schema": JobListings.model_json_schema(),

},

)

jobs = result.extract.get("jobs", [])

print(f"Found {len(jobs)} jobs")Found 62 jobsThe formats=["extract"] tells Firecrawl to run LLM-based extraction. Firecrawl renders the JavaScript, waits for the page to load, and passes the content to an LLM that maps it to your schema.

Saving to CSV

With the data in a list of dictionaries, converting to a DataFrame and saving takes two lines:

df = pd.DataFrame(jobs)

df.to_csv("openai_jobs.csv", index=False)

print(df.head(10).to_string(index=False)) title team location

Backend Software Engineer - B2B Applications B2B Applications 2 locations

Backend Software Engineer, Growth Applied AI Engineering San Francisco

Data Engineer, Analytics Applied AI Engineering San Francisco

Engineering Manager, Atlas Applied AI Engineering San Francisco

Engineering Manager, ChatGPT Growth Applied AI Engineering San Francisco

Engineering Manager, Enterprise Ecosystem Applied AI Engineering Seattle

Engineering Manager, Monetization Infrastructure Engineering Manager San FranciscoSixty-two jobs extracted from a JavaScript-heavy page, parsed into structured data, and saved to disk. No manual HTML parsing, no CSS selectors, no headless browser configuration. That's the scraping workflow: one page, targeted extraction, structured output.

For more scraping patterns, see mastering the Firecrawl scrape endpoint.

Web crawling in action: Blog content collector

Now let's flip the approach. Instead of extracting data from a single page we already know about, we'll discover and collect content from an entire blog. The target: Firecrawl's own blog at firecrawl.dev/blog.

The traditional approach and its problems

A standard crawling workflow would look like this: fetch the blog index, parse all the post links, add them to a queue, visit each one, extract the content, handle pagination if there's more than one index page, and repeat. You'd also need to deduplicate URLs (the same post might be linked from multiple places), respect rate limits, and handle failed requests gracefully.

That's a lot of infrastructure before you've extracted a single piece of content. Most of your code ends up managing the queue and retry logic rather than doing anything useful with the data.

How Firecrawl handles this

Firecrawl's crawl endpoint handles discovery, deduplication, and rate limiting automatically. You give it a starting URL, set boundaries (like staying within /blog/*), and it returns all the pages it finds. Combine this with the JsonFormat extraction we used earlier, and you get structured metadata plus full markdown content for every post in one pass.

Defining the schema

Since we're requesting the markdown format separately, the extraction schema only needs the metadata fields:

from firecrawl import FirecrawlApp

from firecrawl.v2.types import ScrapeOptions, JsonFormat

from pydantic import BaseModel

from dotenv import load_dotenv

import json

import os

load_dotenv()

app = FirecrawlApp(api_key=os.getenv("FIRECRAWL_API_KEY"))

class BlogPost(BaseModel):

title: str

date: strCrawling with extraction

One call handles both discovery and extraction:

result = app.crawl(

"https://www.firecrawl.dev/blog",

limit=100,

include_paths=["/blog/*"],

scrape_options=ScrapeOptions(

formats=[

"markdown",

JsonFormat(

type="json",

prompt="Extract the blog post title and publication date.",

schema=BlogPost.model_json_schema(),

)

]

),

poll_interval=5

)

print(f"Crawled {len(result.data)} pages")Crawled 101 pagesThe include_paths parameter keeps the crawler within the blog section. Without it, the crawler would follow links to documentation, pricing pages, and anywhere else linked from the blog. The limit caps total pages to prevent runaway crawls.

Unlike scrape_url which returns instantly, crawl runs asynchronously. The poll_interval parameter tells the SDK to check for completion every 5 seconds and return once the job finishes.

Processing the results

Each page in result.data contains the extracted JSON, markdown content, and metadata:

posts = []

for page in result.data:

json_data = page.json or {}

if json_data.get("title"):

posts.append({

"title": json_data.get("title"),

"url": page.metadata.source_url if page.metadata else None,

"date": json_data.get("date"),

"content": page.markdown or ""

})

with open("firecrawl_blog_posts.json", "w") as f:

json.dump(posts, f, indent=2)

print(f"Saved {len(posts)} blog posts")Saved 99 blog postsSample output

for post in posts[:3]:

print(f"\n{post['title']}")

print(f" Date: {post['date']}")

print(f" URL: {post['url']}")11 AI Agent Projects You Can Build Today (With Guides)

Date: Sep 18, 2025

URL: https://www.firecrawl.dev/blog/11-ai-agent-projects

Launch Week II - Day 5: Announcing New Actions

Date: Nov 01, 2024

URL: https://www.firecrawl.dev/blog/launch-week-ii-day-5-introducing-two-new-actions

How to Build a Client Relationship Tree Visualization Tool in Python

Date: Mar 07, 2025

URL: https://www.firecrawl.dev/blog/client-relationship-tree-visualization-in-pythonNinety-nine blog posts discovered and extracted from a single API call. No manual link parsing, no queue management, no pagination handling. The scraping section pulled 62 jobs from one page we already knew about. This section collected content from an entire blog without knowing any of the individual URLs upfront. That's the difference between scraping and crawling: targeted extraction versus discovery at scale.

For advanced crawling patterns, see mastering the crawl endpoint.

Popular tools compared for scraping and crawling

The scraping and crawling ecosystem splits into three categories: libraries, frameworks, and API services.

| Tool | Type | Scraping | Crawling | JS Rendering | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BeautifulSoup | Library (Python) | Yes | No | No | Simple HTML parsing |

| Scrapy | Framework (Python) | Yes | Yes | Plugin needed | Large-scale projects |

| Playwright | Library (Multi) | Yes | Manual | Yes | Dynamic pages, testing |

| Crawlee | Framework (JS/TS) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Modern web crawling |

| Firecrawl | API | Yes | Yes | Yes | LLM extraction, quick setup |

Libraries give you the most control but require the most code. You handle requests, parsing, and storage yourself. Frameworks bundle common patterns (request queues, retry logic, data pipelines) so you're not rebuilding infrastructure for every project. API services trade control for speed: you send requests, they handle the infrastructure, you pay per call.

Your choice depends on three things: how much JavaScript rendering you need, whether you want to manage infrastructure, and how often site layouts change.

- If you're scraping static HTML from a handful of pages, BeautifulSoup and requests get the job done.

- If you need to crawl thousands of pages with complex logic, Scrapy or Crawlee give you the scaffolding.

- If you want structured data without writing selectors that break on every redesign, an API like Firecrawl with LLM extraction saves maintenance time.

Even if you don't want to write code to build you web scrapers or crawlers, you can use no-code tools like n8n and Lovable that have native Firecrawl integrations!

P.S: Checkout how you can build AI-powered apps with Lovable and Firecrawl that have access to live web data

Conclusion

Scrapers and crawlers solve different problems. A scraper extracts data from pages you already know about. A crawler discovers pages first, then extracts. One targets a single URL, the other maps out a site.

In practice, most projects use both. You crawl to find all the product pages, then scrape each one for prices and descriptions. You crawl a blog to discover every post, then scrape metadata and content from each. The techniques work together more often than they work alone. When your target pages contain repeating items—product grids, job listings, search results—list crawling adds structure to the extraction step.

Figure out whether you need discovery or just extraction, and the rest follows from there.

FAQs

What is the main difference between web scraping and web crawling?

Scraping extracts data from specific pages you already know about. Crawling discovers pages by following links across a site. Scraping answers "what's on this page?" while crawling answers "what pages exist?"

Can I use scraping and crawling together?

Yes, and most real projects do. A typical workflow crawls a site to discover all relevant URLs, then scrapes each page for structured data. The job listing and blog collector examples in this article show both patterns.

Which is faster, scraping or crawling?

Scraping is faster because you're hitting known URLs directly. Crawling takes longer since it must discover pages, follow links, and handle deduplication. A single scrape call returns in seconds; a crawl job can take minutes depending on site size.

Do I need a crawler if I already have a list of URLs?

No. If you have the URLs, just loop through them and scrape each one. Crawling is only necessary when you need to discover pages you don't know about yet.

How do scrapers handle JavaScript-heavy websites?

Basic HTTP requests only get the initial HTML, which is often empty on modern sites. Tools like Playwright run a headless browser to render JavaScript before extraction. API services like Firecrawl handle rendering automatically.

Should I build my own scraper or use an API service?

Build your own if you need full control, have specific requirements, or want to avoid per-request costs. Use an API service if you want faster setup, don't want to maintain infrastructure, or need features like LLM extraction without writing selector logic.

data from the web