Web scraping turns websites into structured data you can analyze, store, and act on. Price monitoring, lead generation, research aggregation, competitive analysis: all these start with pulling information from web pages programmatically.

Python has become the go-to language for web scraping.

Its readable syntax makes scraping scripts easy to write and maintain, while libraries like Requests, BeautifulSoup, and Selenium handle everything from simple HTTP calls to full browser automation.

This tutorial walks through Python web scraping from the ground up. You'll start with static pages using Requests and BeautifulSoup, move to JavaScript-heavy sites with Selenium, then scale up with async techniques. We'll also cover modern tools like Firecrawl that simplify the entire process. By the end, you'll have working code for each approach and know when to use which tool.

Looking for web scraping project ideas? Check out our collection of Python web scraping projects to put these skills to work.

What Is web scraping with Python?

At its core, python web scraping means writing code that does what you'd do manually: load a page, find the data you want, copy it somewhere useful. The difference is your script can do this thousands of times while you sleep and much faster.

Python became the default choice for this work because its library ecosystem handles every scraping scenario you'll run into:

- Requests and BeautifulSoup cover most static sites in a few lines of code

- Selenium takes over when pages load content with JavaScript

- aiohttp lets you hit hundreds of pages concurrently instead of one at a time

- Scrapy offers a full framework when projects get complex enough to need one

| Tool | Use it when | Main benefit | Notes / limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

requests (HTTP client) | The page is static (data is in the initial HTML response) and you want fast fetching | Fast, simple, lightweight HTTP fetching with control over headers, cookies, retries | Does not execute JavaScript. If content appears only after JS runs, you’ll fetch a mostly empty HTML shell. |

BeautifulSoup (HTML parser) | You already have HTML and need to extract text/links/tables reliably | Easy DOM navigation and forgiving parsing for messy HTML | Parser only (not a downloader or browser). Pair with requests or a rendered HTML source. |

Async HTTP (aiohttp / httpx async) | You need to fetch many pages concurrently (pagination, large URL lists) and pages are mostly static | High throughput via concurrency (many requests in flight) | Requires async code structure. Best when the bottleneck is network latency, not heavy JS rendering. |

Scrapy (crawling framework) | You’re building a crawler (follow links across a site) and need pipelines, scheduling, and scale | Asynchronous scheduling plus built-in crawling patterns (spiders, pipelines, throttling) | Steeper learning curve than requests. JS-heavy sites often need a renderer or hybrid approach. |

Selenium (browser automation) | The site is JavaScript-heavy, requires clicks/infinite scroll, or you need full user-like behavior | Full browser control: runs JS, interacts with UI, handles complex flows | Slower and heavier to scale, more resource-intensive. |

Playwright (modern browser automation) | Similar to Selenium, but you want a more modern stack, often faster, with strong async support | Efficient automation plus strong async support for modern web apps | Still a real browser, so scaling costs remain higher than plain HTTP. |

| Firecrawl (managed scraping API) | You want production reliability without maintaining browsers, plus clean output (markdown/structured data/screenshots) | Simplifies the hard parts: handles JS rendering, returns LLM-ready formats | Slightly less low-level control than a fully custom scraper, but usually worth it for speed and reliability. |

The tricky part isn't fetching pages. It's dealing with everything sites throw at you: inconsistent HTML structures and content that loads after the initial page render.

The tools above handle the basics, but real-world scraping usually means combining several of them with custom logic for each target site.

For a deeper look at other modern library options, see our roundup of open source web scraping libraries.

Scraping static pages with Requests and BeautifulSoup

The simplest scraping targets are static pages.

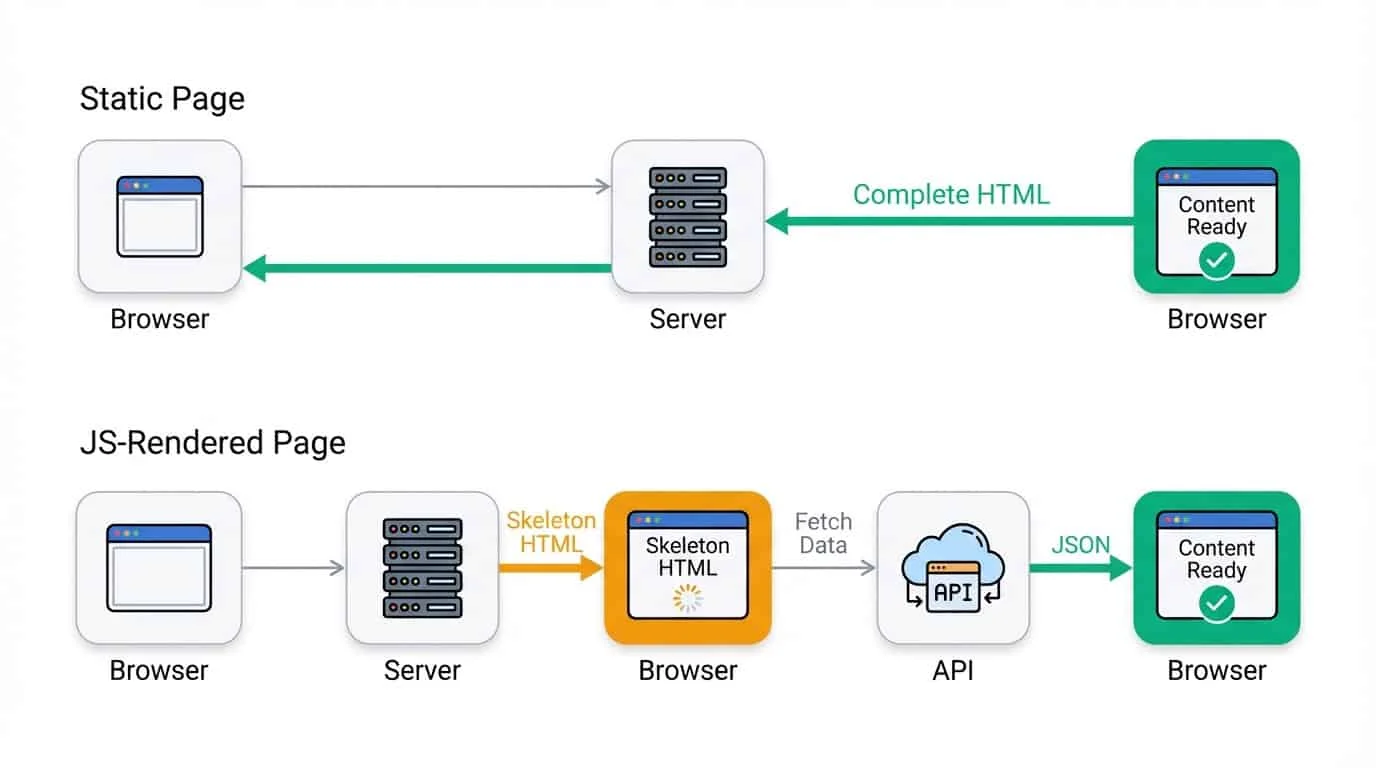

These pages show you everything the moment they load. You click a link, the content appears, done. No spinners, no content popping in a second later, no "Loading..." placeholders. News articles, blog posts, Wikipedia entries, government databases, and plenty of old sites work this way.

Other pages (dynamic websites) load a skeleton first, then fill in the actual content afterward. You might see a brief flash of empty space before products or text appear. Social media feeds, single-page apps, and sites with infinite scroll usually behave like this. Those need different tools.

The quick test: right-click a page and select View Page Source. If you can find the text and data you want in that raw HTML, the page is static and you can scrape it with Requests and BeautifulSoup.

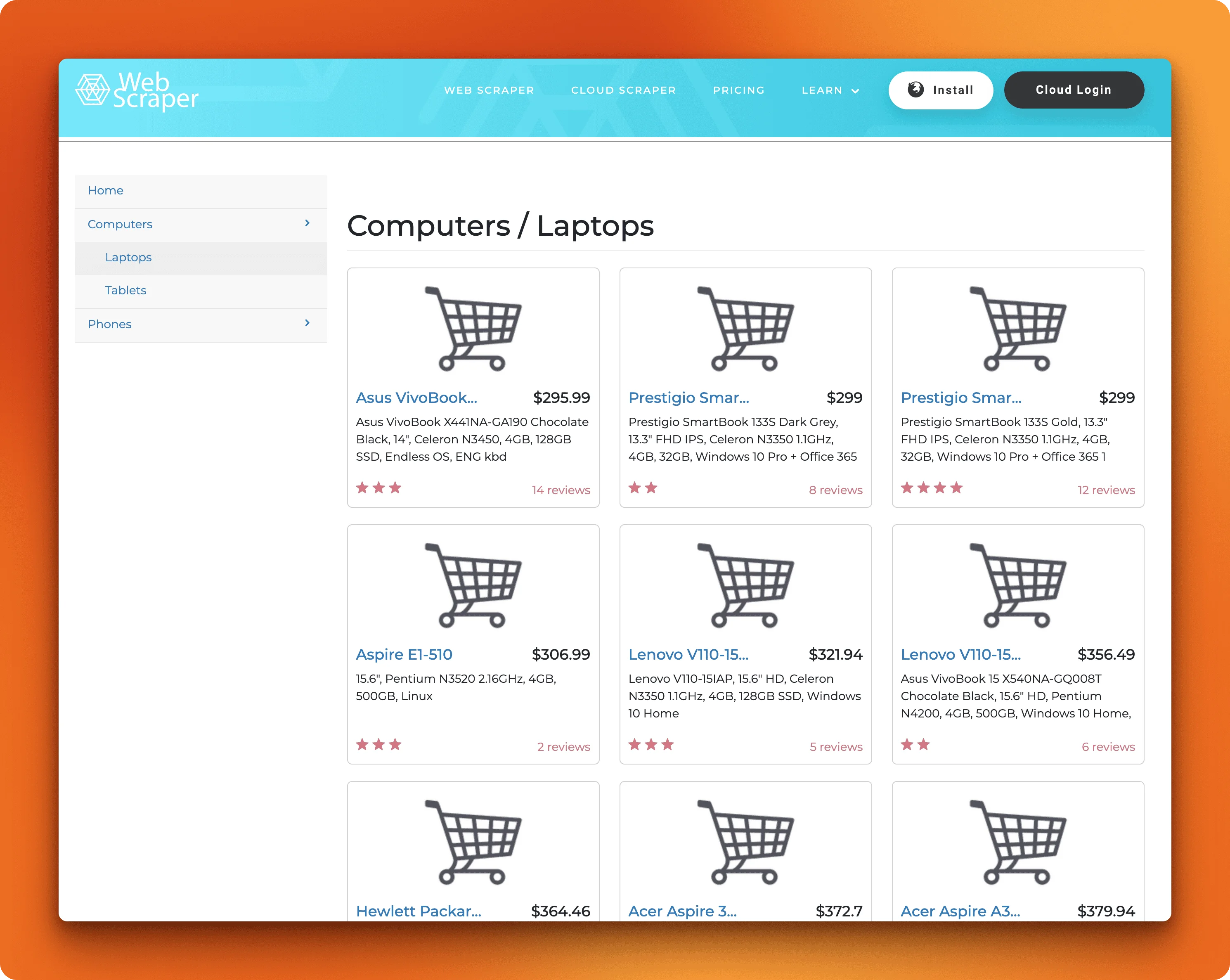

The webscraper.io test site above passes that test. All the laptop names, prices, and specs are right there in the source. Two libraries will get us that data: Requests to fetch the page, BeautifulSoup to parse the HTML and pull out specific elements.

Here's how to get started:

pip install requests beautifulsoup4Start by grabbing the page using the get() method of requests:

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

url = "https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/static/computers/laptops"

response = requests.get(url)

print(response.status_code)200A 200 status code means the request worked. The HTML lives in response.text. Passing it to BeautifulSoup creates a soup object you can search through with special methods:

soup = BeautifulSoup(response.text, "html.parser")

print(type(soup))<class 'bs4.BeautifulSoup'> # The soup objectHow do you find the product structure?

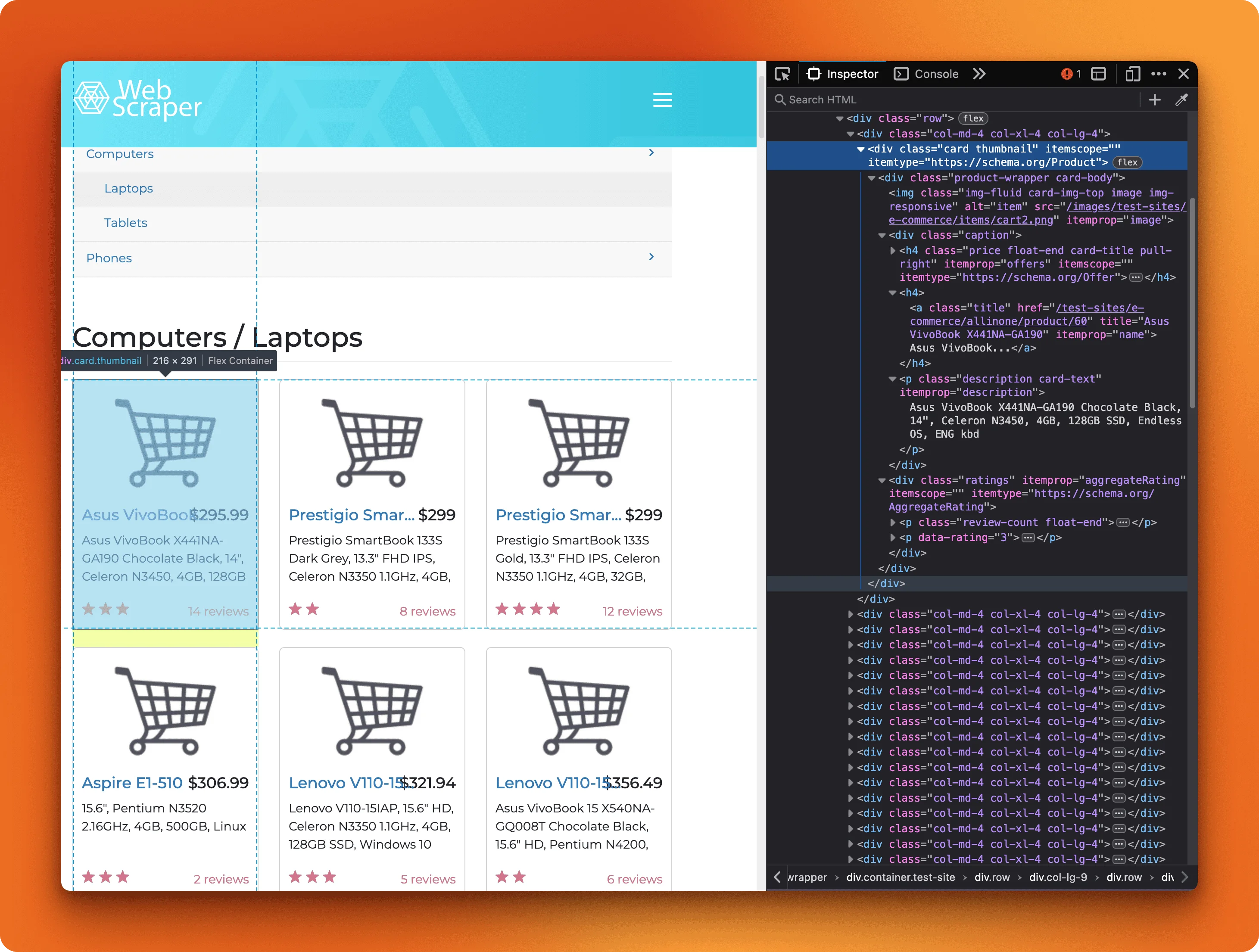

On the webscraper.io test site, open the laptop page in your browser, right-click a product, and hit Inspect. You'll see the HTML behind what's rendered on screen.

Each product card is a div with class thumbnail. Inside that, the price sits in an h4.price tag, the name is an a.title link, and the description is a p.description paragraph.

BeautifulSoup can find these elements a few ways:

# Find the first product card

first_product = soup.find("div", class_="thumbnail")

print(first_product.get_text(strip=True)[:100])$416.99Packard 255 G215.6", AMD E2-3800 1.3GHz, 4GB, 500GB, Windows 8.12That's all the text from one card, mashed together. To get structured data, we need to target specific elements inside it.

If you are completely new to the fundamentals, like how HTML and CSS work, check out our detailed Web Scraping For Beginners article.

Extracting specific fields

Most traditional python web scraping methods use CSS selectors.

CSS selectors work the same way they do in your browser’s DevTools.

The select_one() method grabs the first match:

name = first_product.select_one("a.title").text.strip()

price = first_product.select_one("h4.price").get_text(strip=True)

description = first_product.select_one("p.description").get_text(strip=True)

print(f"Name: {name}")

print(f"Price: {price}")

print(f"Description: {description}")Name: Packard 255 G2

Price: $416.99

Description: 15.6", AMD E2-3800 1.3GHz, 4GB, 500GB, Windows 8.1For attributes like links, use .get():

link = first_product.select_one("a.title").get("href")

print(f"Link: {link}")Link: /test-sites/e-commerce/static/product/31When you're unsure and an element might not exist on some pages, check before accessing it using if/else conditions. So, in our example, we could do:

rating_elem = first_product.select_one("span.rating")

rating = rating_elem.text if rating_elem else "No rating"Scraping all elements

The select() method returns all matches. Loop through them to build a dataset:

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

url = "https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/static/computers/laptops"

response = requests.get(url)

soup = BeautifulSoup(response.text, "html.parser")

products = soup.select("div.thumbnail")

laptops = []

for product in products:

laptops.append({

"name": product.select_one("a.title").text.strip(),

"price": product.select_one("h4.price").get_text(strip=True),

"description": product.select_one("p.description").get_text(strip=True)

})

for laptop in laptops:

print(f"{laptop['name']}: {laptop['price']}")

print(f" {laptop['description']}\n")Packard 255 G2: $416.99

15.6", AMD E2-3800 1.3GHz, 4GB, 500GB, Windows 8.1

Aspire E1-510: $306.99

15.6", Pentium N3520 2.16GHz, 4GB, 500GB, Linux

ThinkPad T540p: $1178.99

15.6", Core i5-4200M, 4GB, 500GB, Win7 Pro 64bit

Aspire E1-572G: $679.00

15.6", Core i5-4200U, 8GB, 1TB, Radeon R5 M240, Windows 8.1

ThinkPad X240: $1311.99

12.5", Core i5-4300U, 8GB, 240GB SSD, Windows 7 Pro 64bit

Latitude E7240: $1003.00

12.5", Core i5-4210U, 4GB, 128GB SSD, Windows 7 Pro 64bitThe data is now in a list of dictionaries, ready for CSV export, database storage, or whatever comes next.

This works for any page where the content you want exists in the initial HTML. When you right-click → View Page Source and see the data, Requests and BeautifulSoup can grab it. The next section covers what happens when that's not the case.

Scraping JavaScript-rendered pages With Selenium

requests + BeautifulSoup aren’t ideal dynamic web scraping tools because they only fetch and parse the initial HTML response, and they don’t run JavaScript that renders most modern sites’ content. For JavaScript-heavy pages, Selenium is usually a better option because it drives a real browser, executes the page scripts, and lets you scrape the fully rendered DOM.

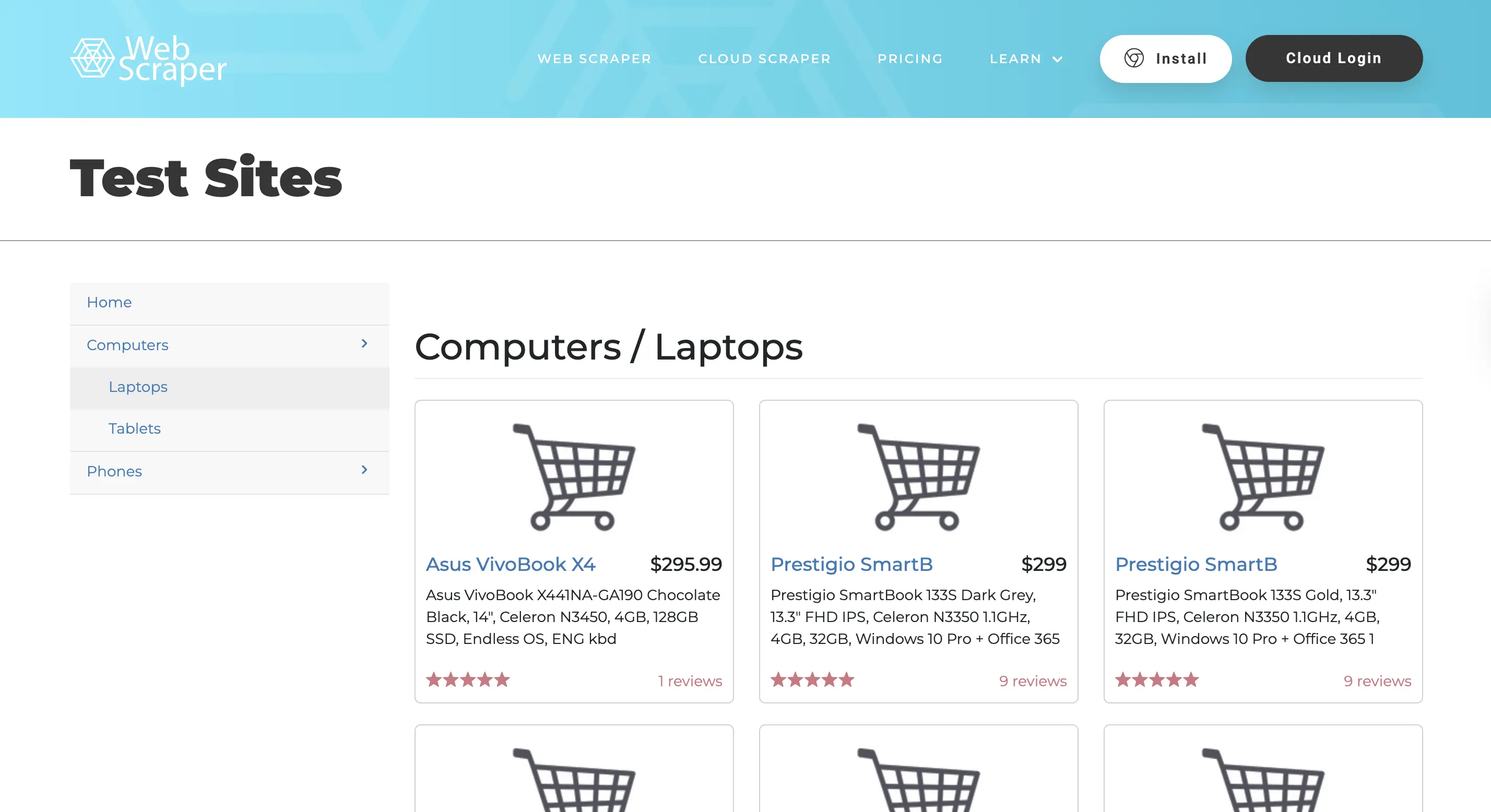

The webscraper.io site has an AJAX version that looks identical to the static one in your browser. Same layout, same products, same prices. AJAX (Asynchronous JavaScript and XML) means the page loads data in the background after the initial HTML arrives, updating the page without a full reload.

Try scraping the AJAX version with Requests:

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

url = "https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/ajax/computers/laptops"

response = requests.get(url)

soup = BeautifulSoup(response.text, "html.parser")

products = soup.select("div.product-wrapper")

print(f"Found {len(products)} products")Found 0 productsThe script returns zero products.

Even though the page loads fine in your browser, but Requests gets nothing.

Right-click and View Page Source on the AJAX version and you'll see why: the product HTML isn't there. The page sends a skeleton, then JavaScript makes separate requests to fetch and render the actual content.

Requests only downloads what the server sends initially. It doesn't run JavaScript, so any content that loads afterward stays invisible. For pages like this, you need a tool that runs a real browser.

How do you set up Selenium?

Selenium controls an actual browser instance. It loads pages, executes JavaScript, waits for content to appear, and lets you interact with elements just like a user would.

pip install seleniumSelenium 4+ includes automatic driver management, so you don't need to download ChromeDriver separately anymore. ChromeDriver is the bridge between Selenium and the Chrome browser; the library now handles matching your Chrome version and downloading the right driver automatically.

from selenium import webdriver

from selenium.webdriver.chrome.options import Options

options = Options()

options.add_argument("--headless") # Run without opening a window

driver = webdriver.Chrome(options=options)

driver.get("https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/ajax/computers/laptops")

print(driver.title)

driver.quit()Web Scraper Test Sites | E-commerce site- This creates a Chrome browser instance,

- loads the page,

- prints its title, and closes the browser.

The --headless flag runs Chrome in the background without displaying a window. Remove it during development when you want to see what's happening. Always call driver.quit() when you're done to close the browser and free up resources.

How do you wait for dynamic content?

Loading a page doesn't mean the content you want is ready. JavaScript needs time to run, make API calls, and render elements. Try grabbing products immediately after driver.get() and you'll get the same empty result as Requests.

Selenium's WebDriverWait solves this by pausing execution until specific conditions are met:

from selenium import webdriver

from selenium.webdriver.common.by import By

from selenium.webdriver.support.ui import WebDriverWait

from selenium.webdriver.support import expected_conditions as EC

from selenium.webdriver.chrome.options import Options

options = Options()

options.add_argument("--headless")

driver = webdriver.Chrome(options=options)

driver.get("https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/ajax/computers/laptops")

# Wait up to 10 seconds for products to appear

products = WebDriverWait(driver, 10).until(

EC.presence_of_all_elements_located((By.CSS_SELECTOR, "div.product-wrapper"))

)

print(f"Found {len(products)} products")

driver.quit()Found 6 productsThe code loads the page, then waits up to 10 seconds for product elements to appear before continuing. Once the products exist in the DOM (the page's internal structure that JavaScript modifies), Selenium returns them and the script proceeds.

WebDriverWait takes the driver and a timeout in seconds. The until() method accepts a condition from the expected_conditions module. Common ones include:

presence_of_element_located: element exists in the DOMpresence_of_all_elements_located: all matching elements existelement_to_be_clickable: element is visible and can receive clicksvisibility_of_element_located: element is visible on the page

If the condition isn't met within the timeout, Selenium raises a TimeoutException. You can catch this to handle pages that fail to load.

Extracting data from Selenium elements

Selenium elements work differently than BeautifulSoup. Use find_element for a single match and find_elements for multiple. The By class specifies how to locate elements:

from selenium import webdriver

from selenium.webdriver.common.by import By

from selenium.webdriver.support.ui import WebDriverWait

from selenium.webdriver.support import expected_conditions as EC

from selenium.webdriver.chrome.options import Options

options = Options()

options.add_argument("--headless")

driver = webdriver.Chrome(options=options)

driver.get("https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/ajax/computers/laptops")

# Wait for products

product_elements = WebDriverWait(driver, 10).until(

EC.presence_of_all_elements_located((By.CSS_SELECTOR, "div.product-wrapper"))

)

# Extract data from the first product

first = product_elements[0]

name = first.find_element(By.CSS_SELECTOR, "a.title").text

price = first.find_element(By.CSS_SELECTOR, "h4.price").text

link = first.find_element(By.CSS_SELECTOR, "a.title").get_attribute("href")

print(f"Name: {name}")

print(f"Price: {price}")

print(f"Link: {link}")

driver.quit()Name: Asus VivoBook X4

Price: $295.99

Link: https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/ajax/product/60After waiting for products, the code grabs the first one and pulls out specific fields.

- Use

.textfor visible text content and.get_attribute("attr_name")for HTML attributes likehreforsrc. - The

Byclass supports several locator strategies:By.CSS_SELECTOR,By.CLASS_NAME,By.ID,By.XPATH, and others.

CSS selectors handle most cases and match what you'd use in BeautifulSoup's select().

Interacting with pages

Selenium can click buttons, fill forms, and scroll pages. The AJAX test site uses pagination buttons to load more products. Clicking them triggers new content without changing the URL.

# Assumes driver is already initialized and page is loaded

next_button = WebDriverWait(driver, 10).until(

EC.element_to_be_clickable((By.CSS_SELECTOR, "button.next"))

)

next_button.click()

# Wait for new products to load

WebDriverWait(driver, 10).until(

EC.presence_of_all_elements_located((By.CSS_SELECTOR, "div.product-wrapper"))

)This waits for the next button to become clickable, clicks it, then waits again for new products to appear. The pattern is: find the element, wait until it's ready, interact, then wait for the resulting content to load. Trying to click an element before it's ready throws an exception.

For infinite scroll pages, you'd scroll to the bottom instead of clicking:

driver.execute_script("window.scrollTo(0, document.body.scrollHeight);")This runs JavaScript directly in the browser, scrolling to the page bottom. Many sites load more content when you reach the end.

Other common interactions:

# Type into an input field

search_box = driver.find_element(By.CSS_SELECTOR, "input.search")

search_box.send_keys("laptop")

# Submit a form

form = driver.find_element(By.CSS_SELECTOR, "form")

form.submit()

# Select from a dropdown

from selenium.webdriver.support.ui import Select

dropdown = Select(driver.find_element(By.CSS_SELECTOR, "select.sort"))

dropdown.select_by_visible_text("Price: Low to High")The send_keys() method types text into input fields. Forms can be submitted directly, and the Select helper class handles dropdown menus.

Complete example: scraping multiple pages

Here's a full script that scrapes products from the first two pages of the AJAX site:

from selenium import webdriver

from selenium.webdriver.common.by import By

from selenium.webdriver.support.ui import WebDriverWait

from selenium.webdriver.support import expected_conditions as EC

from selenium.webdriver.chrome.options import Options

import time

def extract_products(driver):

"""Extract all products currently on the page."""

products = []

elements = driver.find_elements(By.CSS_SELECTOR, "div.product-wrapper")

for el in elements:

products.append({

"name": el.find_element(By.CSS_SELECTOR, "a.title").text,

"price": el.find_element(By.CSS_SELECTOR, "h4.price").text,

})

return products

# Set up driver

options = Options()

options.add_argument("--headless")

driver = webdriver.Chrome(options=options)

try:

driver.get("https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/ajax/computers/laptops")

# Wait for initial products

WebDriverWait(driver, 10).until(

EC.presence_of_all_elements_located((By.CSS_SELECTOR, "div.product-wrapper"))

)

all_products = []

# Get first page

all_products.extend(extract_products(driver))

print(f"Page 1: {len(all_products)} products")

# Click next and get second page

next_button = WebDriverWait(driver, 10).until(

EC.element_to_be_clickable((By.CSS_SELECTOR, "a[rel='next']"))

)

next_button.click()

# Wait for page transition

time.sleep(1)

WebDriverWait(driver, 10).until(

EC.presence_of_all_elements_located((By.CSS_SELECTOR, "div.product-wrapper"))

)

page_2_products = extract_products(driver)

all_products.extend(page_2_products)

print(f"Page 2: {len(page_2_products)} products")

# Print all results

print(f"\nTotal: {len(all_products)} products\n")

for product in all_products:

print(f"{product['name']}: {product['price']}")

finally:

driver.quit()Page 1: 6 products

Page 2: 6 products

Total: 12 products

Packard 255 G2: $416.99

Aspire E1-510: $306.99

ThinkPad T540p: $1178.99

Aspire E1-572G: $679.00

ThinkPad X240: $1311.99

Latitude E7240: $1003.00

Inspiron 15: $389.99

Aspire ES1-520: $287.99

Pavilion 15-dk0056wm: $789.99

Latitude E5540: $949.99

Asus VivoBook X441BA: $399.99

HP 250 G7: $499.99The script defines a helper function to extract products from whatever page is currently loaded, then uses it twice: once for the initial page, once after clicking to page two. The try/finally block guarantees the browser closes even if something goes wrong. The time.sleep(1) gives the page a moment to start its transition before waiting for new products. Without it, WebDriverWait might find the old products still in the DOM and return immediately.

Selenium handles JavaScript-heavy sites that Requests can't touch, but it's slower and more resource-intensive. Each scrape launches an entire browser. The next section covers how to speed things up when you need to hit many pages.

Scraping at Scale With asyncio

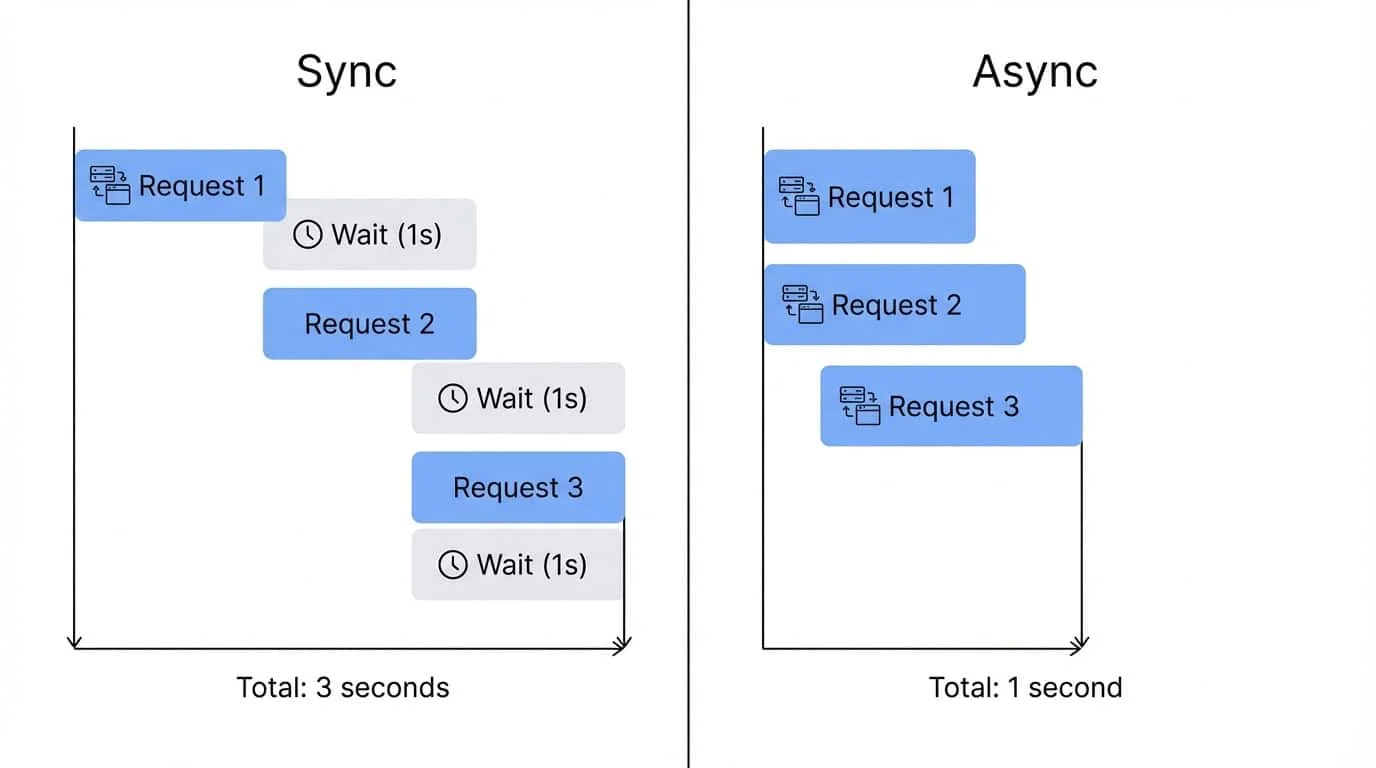

The scripts from previous sections work fine for a handful of pages. But what about scraping with Python an entire product catalog with thousands of URLs? Sequential requests (one after another, waiting for each to complete) turn a ten-minute job into an hour-long crawl.

The bottleneck isn't your CPU or the parsing logic. It's network latency: your script sits idle while bytes travel back and forth. Asynchronous programming solves this by letting you fire off multiple requests and handle responses as they come back, rather than waiting on each one individually.

Python's asyncio module handles this, and aiohttp provides an async-compatible HTTP client.

pip install aiohttpHow does async code differ from regular Python?

Normal Python runs line by line. When you call requests.get(), execution stops there until the response comes back. Nothing else happens during that wait.

Async code can pause a function mid-execution, do other work, then resume where it left off. This requires different syntax because Python needs to know which functions can pause and where the pause points are.

Two new keywords make this work:

async def creates a coroutine instead of a regular function. A coroutine is a function that can be suspended and resumed. You can't call it like a normal function; it needs to be scheduled through the async system.

await marks a pause point. When Python hits an await, it suspends the current coroutine and can run other coroutines while waiting. Once the awaited operation finishes (like a network request completing), execution resumes from that exact spot.

Here's the basic structure:

import asyncio

import aiohttp

async def fetch_page(url):

async with aiohttp.ClientSession() as session:

async with session.get(url) as response:

return await response.text()

async def main():

url = "https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/static/computers/laptops"

html = await fetch_page(url)

print(f"Fetched {len(html)} characters")

asyncio.run(main())Fetched 22147 charactersA few things to unpack here:

asyncio.run(main()) is the bridge between regular Python and async code. It starts the event loop (the scheduler that manages coroutines) and runs your main() coroutine until it finishes. You typically call this once at the entry point of your script.

async with is the async version of a context manager. Regular with statements work fine for synchronous resources, but when the setup or teardown might involve waiting (like opening a network connection), you need async with so other coroutines can run during those waits.

aiohttp.ClientSession() creates a session that manages HTTP connections. It handles connection pooling (reusing connections across requests) and should wrap all your requests rather than creating a new session for each one.

The nested async with session.get(url) as response sends the actual request. The response object streams data, so await response.text() fetches the full body. Both operations can pause the coroutine while waiting for network I/O.

Fetching multiple pages at once

One async request isn't faster than a regular requests.get(). The speedup comes from running multiple coroutines concurrently with asyncio.gather():

import asyncio

import aiohttp

async def fetch_page(session, url):

async with session.get(url) as response:

return await response.text()

async def main():

urls = [

"https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/static/computers/laptops",

"https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/static/computers/tablets",

"https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/static/phones/touch",

]

async with aiohttp.ClientSession() as session:

tasks = [fetch_page(session, url) for url in urls]

results = await asyncio.gather(*tasks)

for url, html in zip(urls, results):

print(f"{url.split('/')[-1]}: {len(html)} chars")

asyncio.run(main())laptops: 22147 chars

tablets: 20194 chars

touch: 19200 charsThe list comprehension [fetch_page(session, url) for url in urls] creates three coroutine objects but doesn't run them yet. asyncio.gather(*tasks) schedules all three to run concurrently. The * unpacks the list into separate arguments.

When execution hits await asyncio.gather(...), all three requests go out at nearly the same time. As each response arrives, its coroutine resumes and finishes. gather() waits until all coroutines complete, then returns their results in the same order as the input.

Total runtime ends up close to the slowest single response, not the sum of all three.

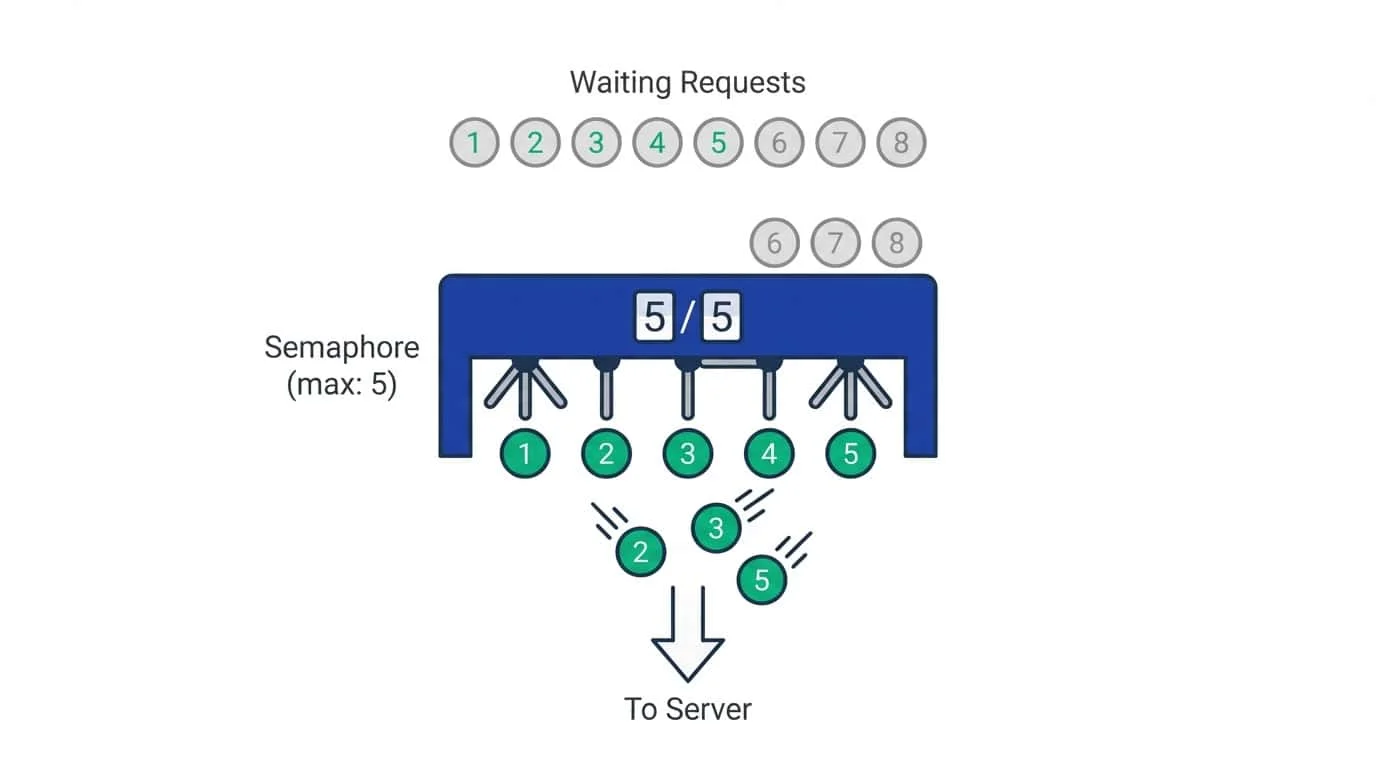

Limiting concurrent requests with a semaphore

For larger batches, blasting a server with hundreds of simultaneous connections is bad practice and will likely get you blocked. A semaphore limits how many requests can run at once.

Think of a semaphore as a counter with a maximum value. Each coroutine that enters the semaphore decrements the counter; when it exits, the counter increments. If the counter hits zero, new coroutines have to wait until someone exits.

import asyncio

import aiohttp

async def fetch_page(session, url, semaphore):

async with semaphore: # Waits here if 5 requests already running

async with session.get(url) as response:

return await response.text()

async def main():

urls = [

"https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/static/computers/laptops",

"https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/static/computers/tablets",

"https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/static/phones/touch",

"https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/static",

]

semaphore = asyncio.Semaphore(5) # Allow max 5 concurrent requests

async with aiohttp.ClientSession() as session:

tasks = [fetch_page(session, url, semaphore) for url in urls]

results = await asyncio.gather(*tasks)

for url, html in zip(urls, results):

print(f"{url.split('/')[-1]}: {len(html)} chars")

asyncio.run(main())With Semaphore(5), at most five requests run at once. If you have 100 URLs, the first five start immediately. As each one finishes and exits the async with semaphore block, another waiting coroutine gets to proceed.

The value you pick depends on the target site and your network. Five to ten is reasonable for most scraping. Higher values speed things up but risk triggering rate limits or overwhelming your own connection.

Complete example: async product scraper

Here's a full script comparing sync vs async on the same three category pages:

import asyncio

import aiohttp

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import time

def parse_products(html):

"""Extract product data from HTML."""

soup = BeautifulSoup(html, "html.parser")

products = []

for card in soup.select("div.thumbnail"):

name_el = card.select_one("a.title")

price_el = card.select_one("h4.price")

if name_el and price_el:

products.append({

"name": name_el.text.strip(),

"price": price_el.text.strip(),

})

return products

# Synchronous version

def scrape_sync(urls):

all_products = []

for url in urls:

response = requests.get(url)

all_products.extend(parse_products(response.text))

return all_products

# Async version

async def fetch_page(session, url, semaphore):

async with semaphore:

async with session.get(url) as response:

return await response.text()

async def scrape_async(urls):

semaphore = asyncio.Semaphore(5)

async with aiohttp.ClientSession() as session:

tasks = [fetch_page(session, url, semaphore) for url in urls]

pages = await asyncio.gather(*tasks)

all_products = []

for html in pages:

all_products.extend(parse_products(html))

return all_products

urls = [

"https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/static/computers/laptops",

"https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/static/computers/tablets",

"https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/static/phones/touch",

]

# Sync timing

start = time.time()

sync_products = scrape_sync(urls)

sync_time = time.time() - start

# Async timing

start = time.time()

async_products = asyncio.run(scrape_async(urls))

async_time = time.time() - start

print(f"Sync: {len(sync_products)} products in {sync_time:.2f}s")

print(f"Async: {len(async_products)} products in {async_time:.2f}s")

print(f"Speedup: {sync_time / async_time:.1f}x")Sync: 18 products in 0.16s

Async: 18 products in 0.05s

Speedup: 3.2xNotice that parse_products() is a regular function, not async. BeautifulSoup parsing is CPU-bound work that happens in memory, so there's nothing to wait on. You only need async def for functions that do I/O like network requests or file operations.

Three pages show a 3x improvement. With more URLs, the gap grows wider since async can keep many requests in flight while sync plods through them one by one.

When isn't async enough?

Async works for static pages where the HTML contains everything you need. Like Requests, aiohttp doesn't run JavaScript, so dynamic content stays invisible.

The tradeoff between tools:

- aiohttp: lightweight, fast for static pages

- Selenium: heavier, slower, but handles JavaScript

You can mix both. Use async to quickly scrape a sitemap or product listing, then send individual product URLs to Selenium when those pages need JavaScript to render. Playwright also has an async API for concurrent browser automation, though it's more resource-intensive than plain HTTP requests.

Modern LLM-ready Python scraping with Firecrawl

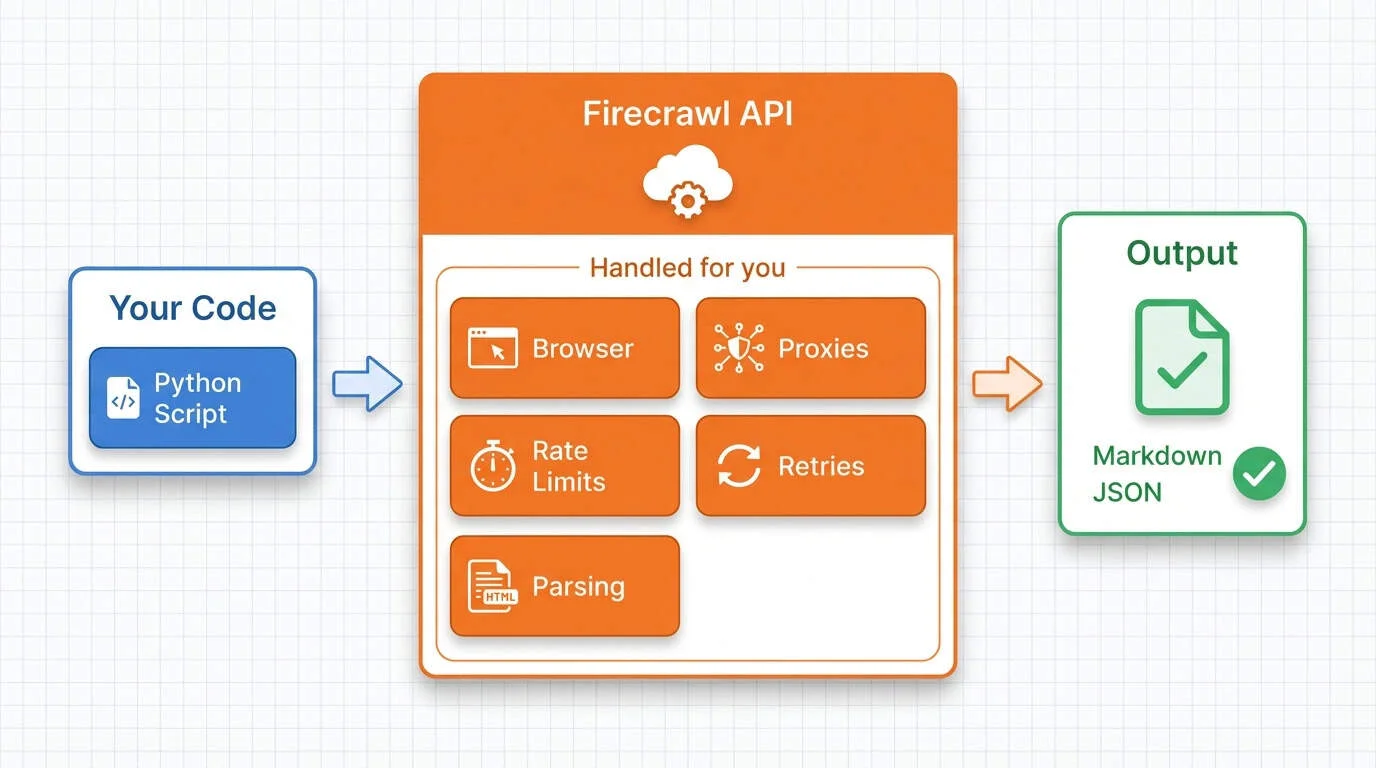

The previous sections built up a stack of tools: Requests and BeautifulSoup for static pages, Selenium for JavaScript, and asyncio for concurrency.

Each layer added capability but also complexity to maintain.

Firecrawl wraps these concerns into a single API to make python web scraping super easy. It runs headless browsers for JavaScript rendering and returns clean markdown or structured JSON instead of raw HTML. Our beginner's guide to web scraping covers the fundamentals; here we'll go deeper into features that replace entire chunks of the code we wrote manually.

Setting up Firecrawl

- Sign up at firecrawl.dev and grab your API key from the dashboard.

- Install the Python SDK:

pip install firecrawl-py python-dotenvStore your API key in a .env file to keep it out of your code:

echo "FIRECRAWL_API_KEY=fc-your-key-here" >> .envThen load it in Python:

from dotenv import load_dotenv

from firecrawl import Firecrawl

load_dotenv()

app = Firecrawl() # Reads FIRECRAWL_API_KEY from environmentThe Firecrawl class reads the API key from your environment automatically. No need to pass it explicitly.

Basic scraping with one API call

Remember the webscraper.io laptop page from earlier sections? With Requests and BeautifulSoup, extracting products took around 20 lines: fetching the page, parsing HTML, selecting elements, pulling text from each field.

Here's the same task with Firecrawl:

from firecrawl import Firecrawl

app = Firecrawl()

result = app.scrape(

"https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/static/computers/laptops",

formats=["markdown"]

)

print(result.markdown[:600])# Test Sites

# Computers / Laptops

#### $416.99

#### [Packard 255 G2](https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/static/product/31)

15.6", AMD E2-3800 1.3GHz, 4GB, 500GB, Windows 8.1

2 reviews

#### $306.99

#### [Aspire E1-510](https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/static/product/32)

15.6", Pentium N3520 2.16GHz, 4GB, 500GB, Linux

2 reviewsThe API returns clean markdown with headings, links, and text already organized. No BeautifulSoup selectors, no parsing logic.

The same call works on JavaScript-heavy pages since Firecrawl runs a browser behind the scenes. No Selenium setup, no explicit waits, no driver management.

The formats parameter controls what you get back. Options include markdown, html, links, screenshot, and json (for structured extraction). You can request multiple formats in one call.

The response also includes metadata you can access:

print(f"Title: {result.metadata.title}")

print(f"URL: {result.metadata.source_url}")Title: Static | Web Scraper Test Sites

URL: https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/static/computers/laptopsExtracting structured data with schemas

Markdown is readable, but most applications need typed data in a predictable shape. Firecrawl can extract specific fields into JSON using a schema. Define what you want with a Pydantic model:

from firecrawl import Firecrawl

from pydantic import BaseModel

from typing import List

class Product(BaseModel):

name: str

price: str

description: str

class ProductList(BaseModel):

products: List[Product]

app = Firecrawl()

result = app.scrape(

"https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/static/computers/laptops",

formats=[{"type": "json", "schema": ProductList.model_json_schema()}]

)

for product in result.json["products"]:

print(f"{product['name']}: {product['price']}")Packard 255 G2: $416.99

Aspire E1-510: $306.99

ThinkPad T540p: $1178.99

ProBook: $739.99

ThinkPad X240: $1311.99

Aspire E1-572G: $581.99The schema tells Firecrawl exactly which fields to pull. It uses language models internally to identify and extract the data, so you don't need to write CSS selectors or worry about HTML structure changes. If a site redesigns its layout but keeps the same content, your schema still works.

The formats parameter accepts a list, so you can mix types. Pass ["markdown", {"type": "json", "schema": ...}] to get both raw content and structured data in one request.

Batch scraping multiple URLs

Earlier we built an async scraper with aiohttp and semaphores to hit multiple pages concurrently. That code handled rate limiting manually with asyncio.Semaphore(5) and required understanding coroutines, gather(), and async context managers.

Firecrawl's batch endpoint handles all of this:

from firecrawl import Firecrawl

app = Firecrawl()

urls = [

"https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/static/computers/laptops",

"https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/static/computers/tablets",

"https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/static/phones/touch",

]

results = app.batch_scrape(urls, formats=["markdown"])

print(f"Scraped {len(results.data)} pages")

for page in results.data:

print(f" {page.metadata.title}: {len(page.markdown):,} chars")Scraped 3 pages

Static | Web Scraper Test Sites: 1,718 chars

Static | Web Scraper Test Sites: 1,582 chars

Static | Web Scraper Test Sites: 1,467 charsOne method call replaces the entire async setup. Firecrawl manages concurrency, rate limiting, and retries server-side. You don't need to worry about overwhelming the target site or managing connection pools. The formats parameter works the same as the single-page scrape, so you can mix markdown, HTML, JSON extraction, and other output types across your batch. For larger batches, use start_batch_scrape() to get a job ID and poll for results asynchronously.

Finding content with search

Sometimes you need data but don't know which URLs contain it. Traditional scraping requires finding pages first, then scraping them separately. Firecrawl's search endpoint combines both steps: search the web and get full page content in one call.

from firecrawl import Firecrawl

app = Firecrawl()

results = app.search(

query="python requests library http tutorial",

limit=3,

scrape_options={"formats": ["markdown"]}

)

print(f"Found {len(results.web)} results\n")

for result in results.web:

title = result.metadata.title

url = result.metadata.source_url

content_len = len(result.markdown)

print(f"{title}")

print(f" URL: {url}")

print(f" Content: {content_len:,} chars\n")Found 3 results

Requests: HTTP for Humans™ — Requests 2.32.5 documentation

URL: https://requests.readthedocs.io/

Content: 15,660 chars

Python's Requests Library (Guide) – Real Python

URL: https://realpython.com/python-requests/

Content: 56,344 chars

Quickstart — Requests 2.32.5 documentation

URL: https://requests.readthedocs.io/en/master/user/quickstart/

Content: 25,407 charsInstead of getting a list of links and snippets like most search APIs, you get the full article content from each result. The scrape_options parameter controls the output format, same as the regular scrape endpoint. This works well for research, competitive analysis, or building datasets from web content. See our search endpoint tutorial for advanced filtering options.

Agent endpoint for autonomous data gathering

The structured extraction we covered earlier uses LLMs to pull specific fields from a page you point it to. You still need to know the URL and define a schema.

The Firecrawl agent endpoint takes this further: describe what you want in natural language, and the agent figures out where to find and how to gather this data.

from firecrawl import Firecrawl

from pydantic import BaseModel

from typing import List

class LaptopSpec(BaseModel):

name: str

price: str

specs: str

class LaptopCatalog(BaseModel):

laptops: List[LaptopSpec]

app = Firecrawl()

result = app.agent(

prompt="Find all laptop products with their names, prices, and specifications",

urls=["https://webscraper.io/test-sites/e-commerce/static/computers/laptops"],

schema=LaptopCatalog.model_json_schema()

)

print(f"Found {len(result.data['laptops'])} laptops:")

for laptop in result.data["laptops"][:3]:

print(f" {laptop['name']}: {laptop['price']}")Found 6 laptops:

Packard 255 G2: $416.99

Dell Latitude 3460: $459.99

Acer Aspire E1-510: $306.99The agent navigates pages, handles pagination, and returns structured data matching your schema. You don't need to figure out how content loads or write clicking/scrolling logic.

The real power shows when you don't provide URLs at all. The agent can search the web to find relevant sources:

from firecrawl import Firecrawl

from pydantic import BaseModel

from typing import List, Optional

class Founder(BaseModel):

name: str

role: Optional[str] = None

class FounderList(BaseModel):

founders: List[Founder]

app = Firecrawl()

result = app.agent(

prompt="Who are the founders of Firecrawl and what are their roles?",

schema=FounderList.model_json_schema()

)

for founder in result.data["founders"]:

print(f"{founder['name']}: {founder['role']}")Eric Ciarla: Co-Founder & CMO

Caleb Peffer: Co-Founder & CEO

Nicolas Silberstein Camara: Co-Founder & CTONo URLs provided, just a question.

The agent searched the web, found relevant pages, extracted the data, and returned it in the schema you specified. This opens up use cases that would require building entire research pipelines manually: competitive intelligence, market research, lead enrichment, fact verification.

The agent is best suited for:

- Complex multi-page extraction where navigation logic would be tedious

- Sites with unknown structure where you'd need to explore first

- Research tasks where relevant URLs aren't known upfront

- One-off data gathering where building a custom scraper isn't worth the effort

Other capabilities

The scrape endpoint supports page interactions through an actions parameter. You can click buttons, fill forms, and scroll to load content before extraction. This handles cases where data appears after user interaction, without managing browser instances yourself.

The crawl endpoint maps entire sites by following links from a starting URL, useful for comprehensive data collection or building sitemaps.

When should you use which tool?

| Tool | Best for | JS Support | Speed | Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Requests + BeautifulSoup | Static pages, learning | No | Fast | Low |

| Selenium | JS-heavy sites, interactions | Yes | Slow | Medium |

| asyncio + aiohttp | High-volume static scraping | No | Very fast | Medium |

| Firecrawl | Production workloads, any site | Yes | Fast | Low |

Traditional tools still have their place. Use Requests and BeautifulSoup when you're learning how scraping works, need precise control over every request, or have a simple one-off task on a static page. They're free and run anywhere Python does.

Firecrawl makes more sense for production workloads where reliability matters, sites that need JavaScript rendering, and projects where you'd rather focus on what to do with data than how to get it. The trade-off is cost: Firecrawl is open-source and you can self-host, but the paid API is much easier to set up and maintain than running the infrastructure yourself. For teams scraping multiple sites over time, the reduced maintenance often outweighs the subscription.

For more on choosing the right approach, see our guide to common web scraping mistakes.

Storing Scraped Data

Scraped data sitting in memory disappears the moment your script ends. You need to save it somewhere. The three most common formats are CSV, JSON, and SQLite, each suited to different use cases. Here we'll focus on practical patterns you can drop into any project.

CSV and JSON export

CSV works best for flat, tabular data. Every spreadsheet application can open it, making CSV the go-to format when non-technical teammates need access to your scraped data.

import csv

def save_to_csv(products, filename):

with open(filename, "w", newline="") as f:

writer = csv.DictWriter(f, fieldnames=products[0].keys())

writer.writeheader()

writer.writerows(products)JSON preserves nested structures and handles complex data types better than CSV. Use it when your scraped data has hierarchy or when you're building data pipelines that consume JSON.

import json

from datetime import datetime

def save_to_json(products, filename):

data = {"scraped_at": datetime.now().isoformat(), "products": products}

with open(filename, "w") as f:

json.dump(data, f, indent=2)The rule of thumb: CSV for flat data you might open in Excel, JSON for nested structures or API consumption.

SQLite for tracking over time

Flat files work fine for one-off scrapes. But if you're monitoring prices, tracking stock levels, or watching content changes, you need a database that can store historical data and answer questions about trends.

SQLite is perfect for this. It's a full SQL database in a single file, built into Python's standard library, and requires no server setup. Add a timestamp column to track when each record was scraped:

import sqlite3

from datetime import date

conn = sqlite3.connect("products.db")

conn.execute("""

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS prices (

product_name TEXT,

price TEXT,

scraped_date TEXT

)

""")

# Insert today's scrape

for product in products:

conn.execute(

"INSERT INTO prices VALUES (?, ?, ?)",

(product["name"], product["price"], date.today().isoformat())

)

conn.commit()Run this daily and you build a price history. Query it to see how prices changed:

history = conn.execute(

"SELECT scraped_date, price FROM prices WHERE product_name = ?",

("MacBook Pro",)

).fetchall()SQLite handles most scraping workloads without breaking a sweat. Consider upgrading to PostgreSQL or a dedicated data warehouse when you need concurrent writes from multiple scrapers or you're storing millions of records.

How do you choose the right format?

Start simple. CSV and JSON require no setup and work for most one-time scraping projects. Graduate to SQLite when you need to track changes over time or query your data with SQL. For production pipelines processing large volumes, PostgreSQL or cloud data warehouses become worth the extra complexity.

Start your python web scraping project today

You've gone from basic HTTP requests to browser automation to async concurrency. That's the full toolkit, and each piece exists because the web keeps finding new ways to make scraping harder.

The manual approach is worth knowing. When something breaks, you'll understand why. When a site does something weird, you'll know which tool to reach for. That knowledge doesn't disappear just because better abstractions come along.

Firecrawl is one of those abstractions. It handles the infrastructure so you can focus on what to do with the data instead of how to get it. Use whichever approach fits the job.

Now go scrape something. Start with the Firecrawl playground - no setup or credit card required.

FAQ

1. What's the difference between web scraping and web crawling?

Crawling follows links across a site to discover pages. Scraping extracts data from those pages. A search engine crawls the web to find pages, then scrapes content to build its index. Most scraping projects do both: crawl to find target URLs, then scrape to pull the data you want.

2. Can I scrape any website?

Technically, if you can view it in a browser, you can scrape it. Practically, some sites make it very hard. Heavy JavaScript rendering and complex page structures create challenges. Simple sites with static HTML are easy. Sites with dynamic content require browser automation tools like Selenium or services like Firecrawl.

3. What's the best Python library for web scraping?

There's no single best library. Requests and BeautifulSoup handle most static pages. Selenium or Playwright work for JavaScript-heavy sites. Scrapy provides a full framework for large projects. Firecrawl wraps common patterns into an API. Pick based on what your target site requires, not what's trending. Our top 10 web scraping tools guide covers more options.

4. How do I scrape images and files?

Grab the URL from the src attribute of img tags or the href of download links, then fetch the file with a separate request. Save the response content in binary mode: open(filename, 'wb').write(response.content). For many files, use async requests to download in parallel.

5. How do I handle pagination?

Find the pattern in page URLs (often a ?page=2 parameter or /page/2 path) and loop through them. For "Load More" buttons or infinite scroll, use Selenium to click or scroll, wait for new content, then extract. Stop when you hit an empty page or reach your target count.

data from the web