From Single URL to Complete Site Map

Website mapping has become more important in modern web development. As sites grow more complex with dynamic content and single-page applications, maintaining a clear understanding of your site's structure and URL hierarchy is necessary for SEO, maintenance, and user experience.

In this guide, we'll examine Firecrawl's /map endpoint, a powerful tool for automated website mapping and URL discovery. We'll cover what it does, why it matters, and how to use it well in your web development workflow.

The /map endpoint helps solve common challenges like keeping track of site structure, identifying broken links, and ensuring search engines can properly crawl and index your content. Let's dive into how it works.

Table of Contents

- From Single URL to Complete Site Map

- Understanding Firecrawl's

/mapEndpoint: Features and Benefits - Step-by-Step Guide to Using the /map Endpoint

- Further Configuration Options for Website Mapping

- Comparing

/crawland/map: When to Use Each Endpoint - Step-by-Step Guide: Creating XML Sitemaps with

/map - Advanced Visualization: Building Interactive Visual Sitemaps with

/map - Mapping the Way Forward

Understanding Firecrawl's /map Endpoint: Features and Benefits

To understand what the /map endpoint does, let's briefly cover what site mapping is and why it's important.

What Is Site Mapping and Why Is It Important for Modern Websites?

Put simply, a sitemap is a list or diagram that communicates the structure of web pages within a website. It's useful for several reasons.

First, it helps developers and site owners understand and maintain their website's structure. A clear overview of how pages are connected makes it easier to manage content, identify navigation issues, and ensure logical flow for users.

Second, sitemaps are important for SEO. Search engines use sitemaps to discover and index pages more quickly. A well-structured sitemap helps ensure that all your important content gets crawled and indexed properly.

Third, sitemaps can help identify potential issues like broken links, orphaned pages (pages with no incoming links), or circular references, making troubleshooting and maintenance much more manageable.

Finally, sitemaps are valuable for planning site improvements and expansions. They provide a bird's-eye view that helps with making strategic decisions about content organization and information architecture.

Guide to Sitemap Types: Visual vs XML Sitemaps

There are two main types of sitemaps: visual and XML.

Visual sitemaps are diagrams or flowcharts that show how websites are structured at a glance. They typically use boxes, lines, and other visual elements to represent pages and their relationships. These visual representations make it easy for team members, designers, and developers to quickly understand site hierarchy, navigation paths, and content organization. They're especially useful during the planning and design phases of web development, as well as for communicating site structure to non-technical team members.

Source: Flowapp

XML sitemaps are shown to the public much less frequently because they contain structured XML code that can look intimidating to non-technical users. However, an XML sitemap is simply an organized file containing all the URLs of a website that search engines can read. It includes important metadata about each URL, such as when it was last modified, how often it changes, and its relative importance. Search engines like Google use this information to crawl websites more intelligently and ensure all important pages are indexed. While XML sitemaps aren't meant for human consumption, they play an important role in SEO and are often required for large websites to achieve optimal search engine visibility.

Source: DataCamp

How Firecrawl's /map Endpoint Solves These Site Mapping Problems

When you're building a website from scratch, you usually need a visual sitemap and can develop the XML one over time as you add more pages. However, if you neglected these steps early on and suddenly find yourself with a massive website (possibly with hundreds of URLs), creating either type of sitemap manually becomes an overwhelming task. This is where automated solutions like the /map endpoint become very useful.

The real challenge of mapping existing sites is finding all the URLs that exist on your website. Without automated tools, you'd need to manually click through every link, record every URL, and track which pages link to others. Traditional web scraping solutions using Python libraries like beautifulsoup, scrapy, or lxml can automate this process, but they can quickly become ineffective when dealing with modern web applications that heavily rely on JavaScript for rendering content, use complex authentication systems, or implement rate limiting and bot detection.

These traditional approaches are time-consuming and error-prone, as it's easy to miss URLs in JavaScript-rendered content, dynamically generated pages, or deeply nested navigation menus.

The /map endpoint addresses these issues and provides the fastest and easiest solution to go from a single URL to a map of the entire website. It is particularly useful in situations where:

- You want to give end-users control over which links to scrape by presenting them with options

- Rapid discovery of all available links on a website is needed

- You need to focus on topic-specific content, you can use the search parameter to find relevant pages

- You only want to extract data from particular sections of a website rather than crawling everything

Step-by-Step Guide to Using the /map Endpoint

Firecrawl is a scraping engine exposed as a REST API, which means you can use it from the command-line using cURL or by using one of its SDKs in Python, Node, Go or Rust. In this tutorial, we will use its Python SDK, so please install it in your environment:

pip install -U firecrawl-pyThe next step is to obtain a Firecrawl API key by signing up at firecrawl.dev and choosing a plan (the free plan is fine for this tutorial).

Once you have your API key, you should save it in a .env file, which provides a secure way to store sensitive credentials without exposing them in your code:

# In your project directory

touch .env

echo "FIRECRAWL_API_KEY='YOUR-API-KEY'" >> .envThen, you should install python-dotenv to automatically load the variables in .env files in Python scripts and notebooks:

pip install python-dotenvThen, using the /map endpoint is as easy as the following code:

from firecrawl import Firecrawl

from dotenv import load_dotenv; load_dotenv()

app = Firecrawl()

response = app.map(url="https://firecrawl.dev")In this code snippet, we're using the Firecrawl Python SDK to map a URL. Let's break down what's happening:

First, we import two main components:

- Firecrawl from the firecrawl package, which provides the main interface to interact with Firecrawl's API

load_dotenvfromdotenvto load our environment variables containing the API access token

After importing, we initialize a Firecrawl instance, which automatically picks up our API access token from the environment variables.

Finally, we make a request to map the URL https://firecrawl.dev using the map() method. This crawls the website and returns information about its structure and pages, taking about two seconds on my machine (the speed may vary based on internet speeds).

Let's look at the response dictionary:

print(f"Response type: {type(response)}")

print(f"Number of links: {len(response.links)}")Response type: <class 'firecrawl.v2.types.MapData'>

Number of links: 379The response is a MapData object with a links attribute containing an array of link objects with additional metadata:

len(response.links)379Each link in the response is now an object that may contain additional metadata:

response.links[0]LinkResult(url='https://www.firecrawl.dev/', title='Firecrawl - The Web Data API for AI', description='The web crawling, scraping, and search API for AI. Built for scale. Firecrawl delivers the entire internet to AI agents and builders. Clean, structured, and ...')Each link is now a LinkResult object with url, title, and description attributes, providing more context about each discovered URL when available.

Further Configuration Options for Website Mapping

Optimizing URL discovery with search parameter

The most notable feature of the endpoint is its search parameter. This parameter allows you to filter the URLs returned by the crawler based on specific patterns or criteria. For example, you can use it to only retrieve URLs containing certain keywords or matching specific paths. This makes it very useful for focused crawling tasks where you're only interested in a subset of pages for massive websites.

Let's use this feature on the Stripe documentation and only search for pages related to taxes:

url = "https://docs.stripe.com"

response = app.map(url=url, search="tax")The response structure will be the same:

[link.url for link in response.links[:10]]['https://docs.stripe.com/tax',

'https://docs.stripe.com/tax/how-tax-works',

'https://docs.stripe.com/tax/tax-codes',

'https://docs.stripe.com/tax/products-prices-tax-codes-tax-behavior',

'https://docs.stripe.com/tax/calculating',

'https://docs.stripe.com/tax/reports',

'https://docs.stripe.com/tax/zero-tax',

'https://docs.stripe.com/api/tax/calculations/create',

'https://docs.stripe.com/api/tax/calculations',

'https://docs.stripe.com/tax/supported-countries/united-states']Let's count up the found links:

len(response.links)2954Nearly 3000 in only three seconds!

Essential /map parameters for customized site mapping

The /map endpoint accepts several additional parameters to control its behavior:

search

- Type: string

- Description: Filter links containing specific text to find topic-relevant pages.

limit

- Type: integer

- Default: 100

- Description: Specifies the maximum number of URLs the crawler will return in a single request. This helps manage response sizes and processing time.

sitemap

- Type: string

- Default: "include"

- Options: "only", "include", "skip"

- Description: Controls how the crawler handles sitemap files:

- "only": Returns URLs exclusively from sitemap files

- "include": Includes sitemap URLs along with discovered links

- "skip": Ignores sitemap files completely

include_subdomains

- Type: boolean

- Default: True

- Description: Controls whether the crawler should follow and return links to subdomains (e.g., blog.example.com when crawling example.com), providing a comprehensive view of the entire web property.

Let's try running the Stripe example by including some of these parameters, like the sitemap set to "only" and include_subdomains turned on:

url = "https://docs.stripe.com"

response = app.map(url=url, search="tax", sitemap="only", include_subdomains=True)

len(response.links)3436This time, the link count increased.

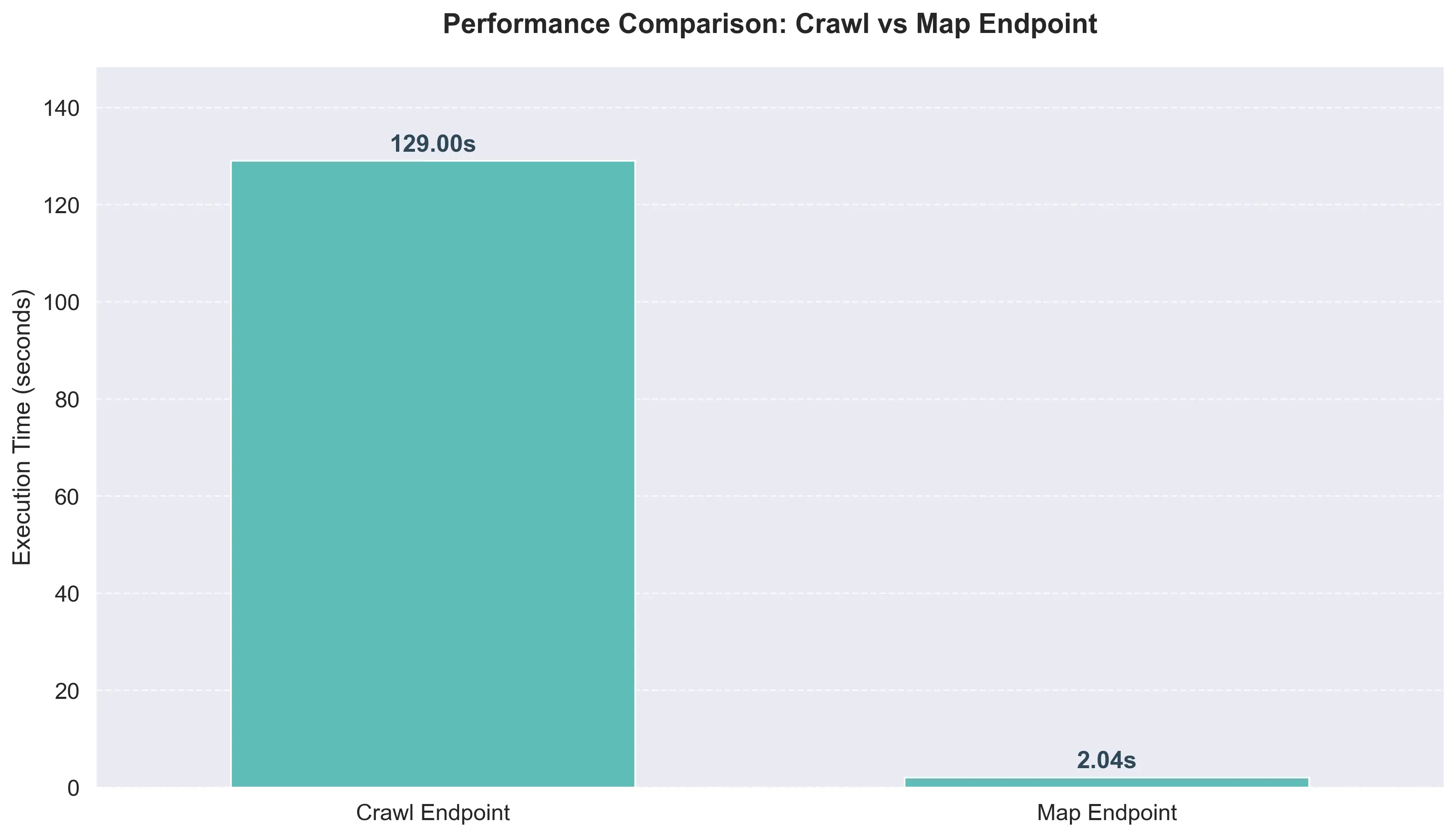

Comparing /crawl and /map: When to Use Each Endpoint

If you've read our separate guide on the /crawl endpoint of Firecrawl, you may notice one similarity between it and the /map endpoint.

If you set the response format of crawl to "links", you'll also get a list of URLs found on the website. While the purpose is the same, there are major performance differences.

First, the /crawl endpoint is much slower for URL discovery, as shown by the execution times in the examples below:

# In Jupyter Notebook

%%time

url = "https://books.toscrape.com"

crawl_response = app.crawl(url=url, limit=100)CPU times: user 45 ms, sys: 12 ms, total: 57 ms

Wall time: 11.6s%%time

url = "https://books.toscrape.com"

map_response = app.map(url=url)CPU times: user 2.1 ms, sys: 1.8 ms, total: 3.9 ms

Wall time: 1.4s

This is because /crawl needs to fully load and parse each page's HTML content and extract structured data, while /map is optimized specifically for URL discovery, making it much faster for sitemap generation and link analysis.

The /map endpoint prioritizes speed and discovers URLs more efficiently:

print(f"Crawl found: {len(crawl_response.data)} pages")

print(f"Map found: {len(map_response.links)} links")Crawl found: 100 pages

Map found: 1228 linksThe /map endpoint excels at rapid URL discovery across the entire site, while /crawl focuses on extracting detailed content from individual pages.

Due to its speed and comprehensive URL discovery, /map provides an excellent foundation for sitemap generation, making it the ideal choice for this use case.

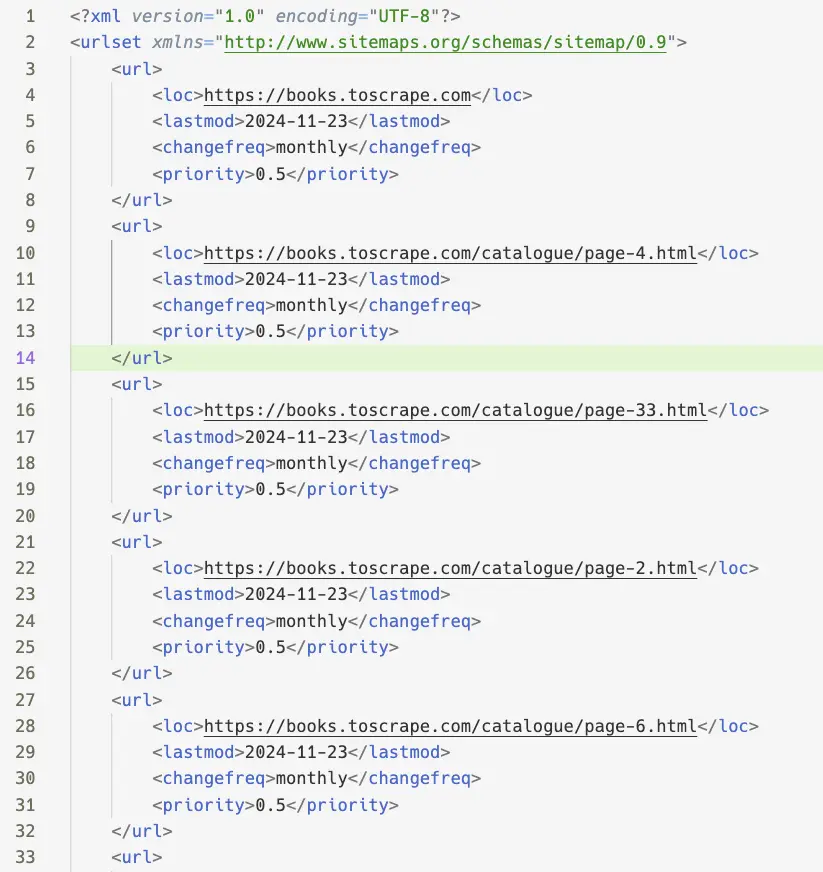

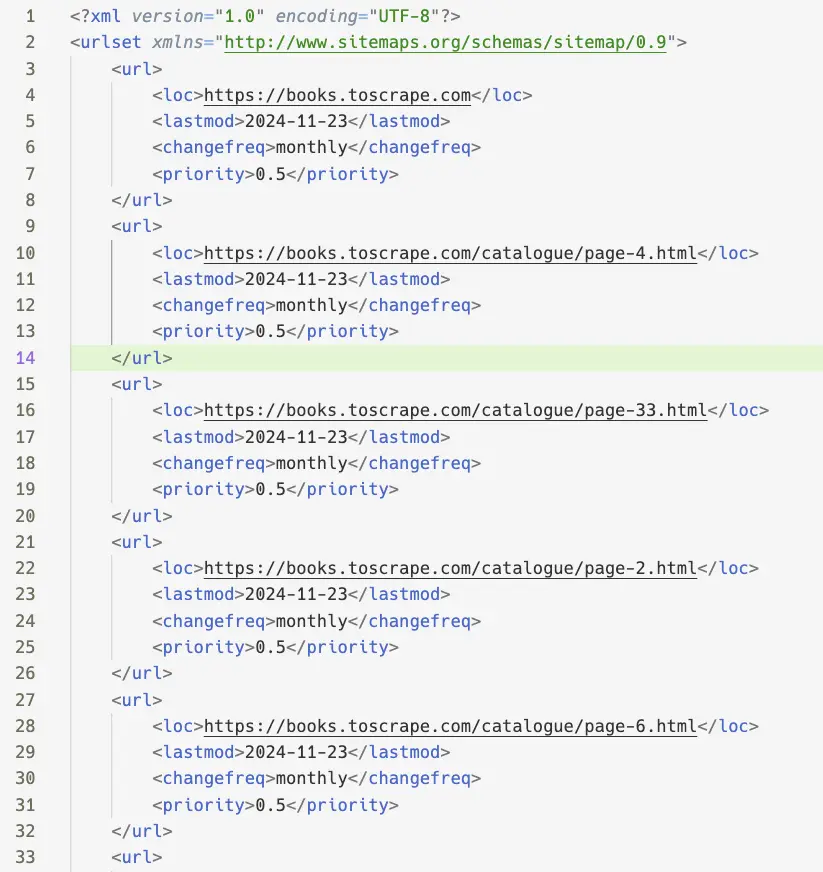

Step-by-Step Guide: Creating XML Sitemaps with /map

Now, let's see how to convert the links found with /map into an XML sitemap using Python. We'll need to import the following packages:

from datetime import datetime

import xml.etree.ElementTree as ET

from urllib.parse import urlparseWe'll use:

datetime: To add timestamps to our sitemap entriesxml.etree.ElementTree: To create and structure the XML sitemap fileurllib.parse: To parse and validate URLs before adding them to the sitemap

Let's start by defining a new function - create_xml_sitemap:

def create_xml_sitemap(urls, base_url):

# Create the root element

urlset = ET.Element("urlset")

urlset.set("xmlns", "http://www.sitemaps.org/schemas/sitemap/0.9")In the function body, we first create the root XML element named "urlset" using ET.Element(). Then we set its xmlns attribute to the sitemap schema URL http://www.sitemaps.org/schemas/sitemap/0.9 to identify this as a valid sitemap XML document.

Next, we get the current date to provide a last modified date (since /map doesn't return the modification dates of pages):

def create_xml_sitemap(urls, base_url):

# Create the root element

...

# Get current date for lastmod

today = datetime.now().strftime("%Y-%m-%d")Then, we add each URL to the sitemap:

def create_xml_sitemap(urls, base_url):

...

# Add each URL to the sitemap

for url in urls:

# Only include URLs from the same domain

if urlparse(url).netloc == urlparse(base_url).netloc:

url_element = ET.SubElement(urlset, "url")

loc = ET.SubElement(url_element, "loc")

loc.text = url

# Add optional elements

lastmod = ET.SubElement(url_element, "lastmod")

lastmod.text = today

changefreq = ET.SubElement(url_element, "changefreq")

changefreq.text = "monthly"

priority = ET.SubElement(url_element, "priority")

priority.text = "0.5"The loop iterates through each URL in the provided list and adds it to the sitemap XML structure. For each URL, it first checks whether the domain matches the base URL's domain to ensure we only include URLs from the same website. If it matches, it creates a new <url> element and adds several child elements:

<loc>: Contains the actual URL<lastmod>: Set to today's date to indicate when the page was last modified<changefreq>: Set to "monthly" to suggest how often the page content changes<priority>: Set to "0.5" to indicate the relative importance of the page

This creates a properly formatted sitemap entry for each URL following the Sitemap XML protocol specifications.

After the loop finishes, we create and return the XML string:

def create_xml_sitemap(urls, base_url):

...

# Add each URL to the sitemap

for url in urls:

...

# Create the XML string

return ET.tostring(urlset, encoding="unicode", method="xml")Here is the full function:

def create_xml_sitemap(urls, base_url):

# Create the root element

urlset = ET.Element("urlset")

urlset.set("xmlns", "http://www.sitemaps.org/schemas/sitemap/0.9")

# Get current date for lastmod

today = datetime.now().strftime("%Y-%m-%d")

# Add each URL to the sitemap

for link in urls:

# Handle LinkResult objects from v2 response

url = link.url if hasattr(link, 'url') else str(link)

# Only include URLs from the same domain

if urlparse(url).netloc == urlparse(base_url).netloc:

url_element = ET.SubElement(urlset, "url")

loc = ET.SubElement(url_element, "loc")

loc.text = url

# Add optional elements

lastmod = ET.SubElement(url_element, "lastmod")

lastmod.text = today

changefreq = ET.SubElement(url_element, "changefreq")

changefreq.text = "monthly"

priority = ET.SubElement(url_element, "priority")

priority.text = "0.5"

# Create the XML string

return ET.tostring(urlset, encoding="unicode", method="xml")Let's use the function on the links returned by the last /map endpoint use:

base_url = "https://books.toscrape.com"

links = map_response.links

xml_sitemap = create_xml_sitemap(links, base_url)

# Save to file

with open("test_generated_sitemap.xml", "w", encoding="utf-8") as f:

f.write('<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>\n')

f.write(xml_sitemap)Here is what the file looks like after saving:

Such a test_generated_sitemap.xml file provides a standardized way for search engines to discover and crawl all pages on your website.

Advanced Visualization: Building Interactive Visual Sitemaps with /map

If you want a visual sitemap of a website, you don't have to sign up for expensive third-party services and platforms. You can automatically generate one using the /map endpoint, Plotly, and a few other libraries.

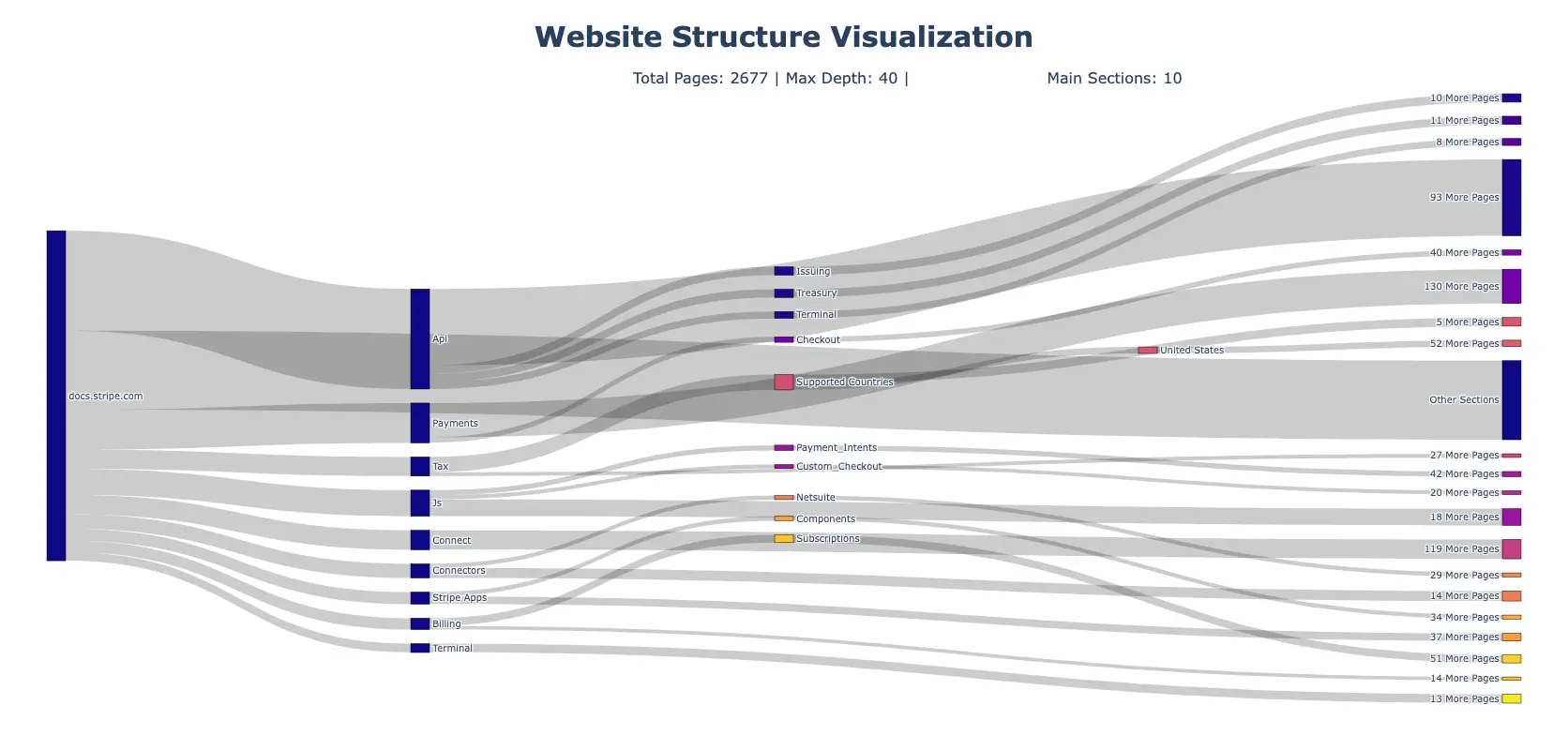

The resulting graph would look like the following:

The Sankey diagram above visualizes the hierarchical structure of the Stripe documentation (which is quite large) by showing how pages are organized and connected across different sections. The width of each flow represents the number of pages in that section, making it easy to identify which parts of the website contain the most content. The colors help distinguish between different sections and subsections.

The diagram starts from a central root node and branches out into the website's main sections. Each section can then split further into subsections, creating a tree-like visualization of the site's architecture. This makes it simple to understand the overall organization and identify potential navigation or structural issues.

For example, you can quickly spot which sections are the largest (the API section), how content is distributed across different areas, and whether there's logical grouping of related pages. This visualization is especially useful for content strategists, SEO specialists, and web architects who need to analyze and improve website structure.

The script that generated this plot contains more than 400 lines of code and is fully customizable. The code in sitemap_generator.py (available in both v1 and v2 versions) follows a modular, object-oriented approach with several main components:

- A

HierarchyBuilderclass that analyzes URLs returned by/mapor/crawland builds a tree-like data structure up to 4 levels deep. - A

SankeyDataPreparatorclass that transforms this hierarchy into a format suitable for visualization, using thresholds to control complexity - A

SitemapVisualizerclass that creates the final Sankey diagram with proper styling and interactivity

The script automatically handles grouping smaller sections together, truncating long labels, generating color schemes, and adding hover information (the generated plots are all interactive through Plotly). All aspects can be customized through parameters, including minimum branch size, relative thresholds, label length, and color schemes.

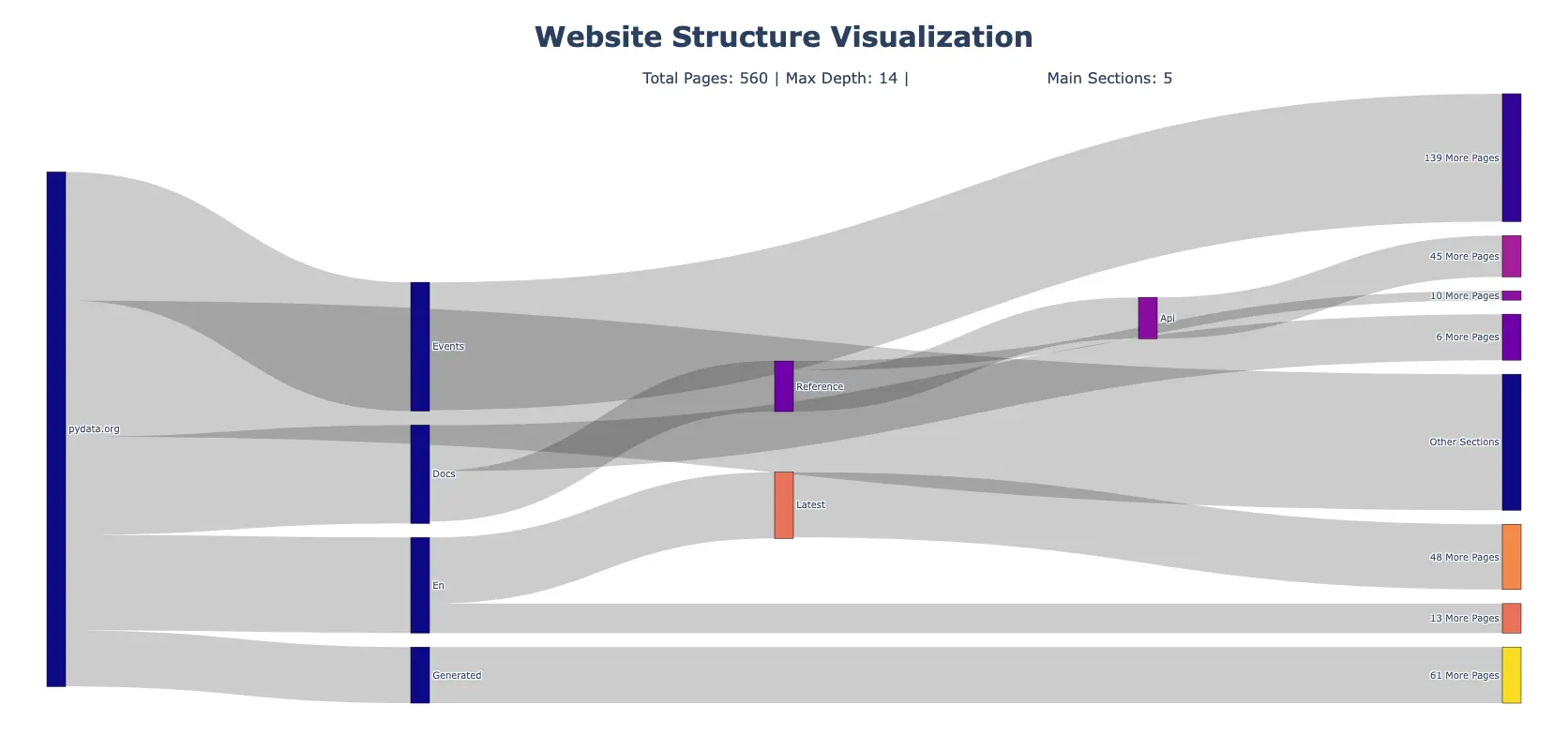

Here is another plot generated for the PyData.org website:

Mapping the Way Forward

The /map endpoint represents a powerful tool in the modern web developer's toolkit, offering a fast way to discover and analyze website structures with major advantages:

- Speed: As shown, it's much faster than traditional crawling methods, making it ideal for quick site analysis

- Adaptability: With parameters like

search,sitemap, andinclude_subdomains, it can be tailored to specific needs - Practical Applications: From generating XML sitemaps for SEO to creating visual site hierarchies, the endpoint serves multiple use cases

While it may not capture every single URL compared to full crawling solutions, its speed and ease of use make it an excellent choice for rapid site mapping and initial structure analysis. As the endpoint continues to develop, its combination of performance and accuracy makes it an increasingly useful tool for website maintenance, SEO improvement, and content strategy.

To discover what more Firecrawl has to offer, be sure to read the following related resources:

Frequently Asked Questions

How fast is Firecrawl's /map endpoint?

The /map endpoint typically processes websites in 2-3 seconds, compared to several minutes with traditional crawling methods.

Can I use the /map endpoint for large websites?

Yes, the /map endpoint can handle large websites with a current limit of 5000 URLs per request, making it suitable for most medium to large websites.

What's the difference between XML and visual sitemaps?

XML sitemaps are machine-readable files used by search engines for indexing, while visual sitemaps provide a graphical representation of website structure for human understanding and planning.

data from the web